Quick Memory Tips That Actually Work

Most forgetting isn't really forgetting. It's failing to remember in the first place. If your mind was wandering or you were half-distracted, the memory never had a chance to form.

The good news: once you understand how memory actually works, you can dramatically improve it. The tips on this page are backed by decades of research, and you can start using them immediately.

I've organized these strategies around the three stages of learning: getting ready to learn, encoding information deeply, and reviewing strategically. Within each stage, you'll find specific techniques that research has shown to be effective.

After reading these tips, you might also want to check out my quick guide to how memory works. And for a deeper dive into memory improvement, see my Get a Better Memory page.

Part 1: Before You Learn (Get Your Brain Ready)

Your "attention" is how tightly you focus on new information. Without truly paying attention, a memory simply cannot form. Memory expert Harry Lorayne calls this "Original Awareness." Think of it like a camera: if you don't actually press the shutter button, there's no photo to look at later.

Before you try to learn anything important, take a moment to get your brain into the right state.

Get moving first. Physical movement increases blood flow to your brain. Before a study session, take a brisk walk, do some jumping jacks, or climb a flight of stairs. Research consistently shows that even brief exercise enhances cognitive function and memory through neuroplastic changes in the brain. You don't need a full workout. Even 5-10 minutes of movement can prime your brain for better learning.[1]

Breathe slowly and deeply. Many people are shallow breathers without realizing it. Before learning, take several slow, deep breaths from your belly. Slow, controlled breathing is associated with changes in brain activity that support memory encoding and retrieval. It also reduces the anxiety that can block learning.[2]

Eliminate distractions ruthlessly. This sounds obvious, but most people underestimate how much distractions hurt memory formation. Put your phone in another room. Close unnecessary browser tabs. Tell people you'll be unavailable. The cost of switching attention is higher than most people realize.

Hydrate. Don't reach for sodas or energy drinks; they'll just cause you to crash. Instead, drink a glass of water. Many people are mildly dehydrated without knowing it, and your brain is sensitive to hydration status. Drink that water, and you'll almost certainly feel more alert.

Use time boxes. When you need to study new information, set a timer. Give yourself a defined amount of time (30-50 minutes works well for most people), then take a short break. This constraint forces focus because you know your time is limited. It's similar to the Pomodoro Technique, and it works.

Try to answer before you learn. Here's a counterintuitive finding: attempting to answer a question before you've learned the material improves how well you learn it, even when you get the initial answer wrong. The failed attempt primes your brain to encode the correct answer more deeply when you encounter it. Before reading a chapter, look at the headings and try to guess what you'll learn. Before a lecture, try to answer the topic questions. You'll be wrong, but you'll remember better.[3]

Part 2: While You Learn (Encode Deeply)

Once you're focused and ready, how you engage with new material determines whether it sticks. Passive reading is one of the least effective ways to learn, despite how natural it feels. The techniques below force deeper processing.

Generate, Don't Just Read

Research on the "generation effect" consistently shows that information you produce yourself is remembered better than information you simply read. Across 86 studies, generating information produced almost half a standard deviation better memory than passive reading.[4]

What does this mean practically?

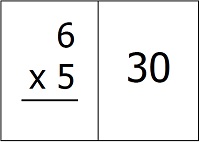

Fill in the blanks. Instead of reading "The capital of France is Paris," cover the answer and try to produce it: "The capital of France is ____." The effort of generation strengthens the memory trace.

Close the book and recite. After reading a section, close the book and try to state the main points from memory. Don't just think about whether you could do it. Actually do it. This is harder and more effective.

Write by hand. Research suggests that writing by hand is more effective than typing for learning concepts. Because handwriting is slower, you're forced to summarize and process rather than transcribe verbatim. The physical act of writing also engages different brain pathways than typing.[5]

Explain it to someone (real or imaginary). If you can teach a concept clearly so that someone else understands it, you truly know it. Even explaining to an empty room or a rubber duck forces you to generate rather than recognize.

Ask "Why Does This Make Sense?"

Elaborative interrogation is a technique where you ask yourself why a fact is true and then generate an explanation. This forces you to connect new information to what you already know, creating more memory pathways.[6]

For example, if you're learning that "copper is a good conductor of electricity," don't just read it. Ask yourself: Why would copper conduct electricity well? Then generate an answer (something about electrons being loosely bound in metals). Even if your explanation isn't perfect, the act of generating it deepens the memory.

This works especially well when you have relevant prior knowledge to draw on. If you're learning something completely unfamiliar, you might need to build foundational knowledge first.

Use Multiple Sensory Channels

Your brain processes visual and verbal information through separate pathways. When you engage both, you create multiple routes to the same memory. If one pathway fails during recall, the other might still work.

Combine words and images. When learning something, don't just read about it. Look at a diagram. Draw a sketch. Create a mental picture. Research on dual coding shows that information encoded both verbally and visually is remembered better than information encoded through only one channel.[7]

Say it out loud. Reading silently uses only visual processing. Reading aloud adds auditory processing. Abraham Lincoln used this technique, reading important documents aloud to encode them more deeply.

Do it. If you're learning a procedure, don't just read about it. Actually perform it. Motor memory is a separate system from declarative memory, and using both creates stronger overall encoding.

Emotionalize it. Find some way to connect emotionally with the material. Anything emotional will be far easier to remember. It can make you sad or happy or intrigued. It doesn't matter, but you must find some way to care about the material.

Chunk Large Information

When facing a large amount of information, break it into smaller, manageable pieces. For example, phone numbers are easier to remember as three chunks (555-867-5309) than as a long string of digits. Research suggests that working memory can hold about 7 items (plus or minus 2) at a time. Chunking lets you work within this limit while remembering more total information.[8]

Group related concepts together. Create hierarchies. Find the structure in what you're learning. The more organized the information is in your mind, the easier it is to retrieve.

Visualize Vividly (and Strangely)

Your brain is wired to remember images far better than abstract words or concepts. Neuroscience research confirms that visual mental imagery activates many of the same brain areas as actual perception, essentially giving you a "second exposure" to the material. This is why visualization is the foundation of nearly every powerful memory technique, from the ancient memory palace to modern linking methods.[22]

But here's the key: ordinary mental images don't stick. What sticks is the bizarre, the exaggerated, the emotionally charged. Memory researchers call this the "distinctiveness effect." When an image stands out as strange or unexpected, your brain flags it as important and encodes it more deeply.

Here's how to use visualization effectively:

Make it weird. Trying to remember that your meeting is in Room 7? Don't just picture a door with "7" on it. Instead, visualize seven dwarfs bursting out of the door singing, or a giant number 7 made of neon lights crashing through the wall. The stranger the image, the more memorable.

Make it move. Static images are forgettable. Animated scenes stick. If you're memorizing that iron is Fe on the periodic table, don't just picture iron. Imagine a giant iron beam crashing down with the letters "Fe" painted on it, sparks flying everywhere.

Exaggerate size and quantity. A dog is forgettable. A dog the size of a building, or a thousand tiny dogs swarming, is not. When creating mental images, go big or go tiny, go numerous or singular. Extreme is memorable.

Involve yourself. Images where you're a participant tend to be more vivid than scenes you merely observe. Instead of watching that giant number 7 crash through the wall, imagine you're riding on top of it.

Use established systems. Techniques like the Method of Loci (memory palace) and the Link Method provide frameworks for creating and organizing vivid mental images. These systems have been used for thousands of years because they work.

The effort of creating strange, vivid mental images might feel silly at first. But this silliness is precisely what makes them stick. Your brain pays attention to the unusual and discards the mundane.

Part 3: After You Learn (Review Strategically)

How you review matters more than how much you review. The research here is very clear: some review strategies are dramatically more effective than others.

Test Yourself (Don't Just Re-read)

This is one of the most robust findings in memory research. Testing yourself on material produces far better long-term retention than simply re-reading it, even when the time spent is equal. This is called "active recall" or "retrieval practice."[9]

The frustrating part: re-reading feels more effective. The material seems familiar, so you conclude you know it. But recognition is not the same as recall. When the test comes and you have to produce the answer from scratch, that familiarity won't help you.

Use flash cards. Write key facts on index cards. On the front, write the question or concept. On the back, write the answer. Test yourself by trying to produce the answer before flipping the card. Apps like Anki and Quizlet make digital flash cards easy to create and review.

Quiz yourself constantly. Every few minutes while studying, pause and try to state what you've just learned. If you can't remember much, that's valuable feedback: you need to go back and engage more deeply.

Practice retrieval, not recognition. Multiple choice is easier than free recall because you only have to recognize the right answer. But free recall (producing the answer from nothing) builds stronger memories. When you can, practice the harder form.

Space Out Your Reviews

One of the most powerful and well-researched memory techniques is spaced repetition. Instead of cramming all your studying into one marathon session, spread your learning out over time with increasing intervals between reviews.

German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus discovered the "forgetting curve" back in the 1880s. His research showed that we forget information at a remarkable rate unless we actively review it. But here's the good news: if you review at strategic intervals, the rate of forgetting slows dramatically, and the memory becomes more durable.[10]

A meta-analysis of dozens of studies confirms that spacing out your learning beats cramming every time. Neuroscience research shows that spacing taps different molecular mechanisms than massed practice, helping memories consolidate properly.[11][12]

Review soon after learning. Go over new material within the first hour. This is when forgetting happens fastest, so a quick review at this point has an outsized impact.

Then space out your reviews. After your initial review, wait a day before reviewing again. Then wait two or three days. Then a week. Then two weeks. Each time you successfully recall the information, you can wait longer before the next review.

Use spaced repetition software. Apps like Anki automate the scheduling of your reviews. They track what you know and what you're struggling with, and they present material at optimal intervals for retention. This takes the guesswork out of when to review.

Don't cram. Research consistently shows that cramming produces short-term recall but poor long-term retention. If you have a week to study for a test, you'll remember more by studying a little each day than by pulling an all-nighter the day before.[11]

Interleave Different Topics

Here's a counterintuitive finding that most students don't know about: mixing different topics or problem types during practice produces better long-term learning than practicing one topic at a time until you've mastered it.[13]

This is called "interleaving," and it can improve test performance by 50% or more compared to blocked practice. In one study, physics students who alternated between problem types during homework scored dramatically higher on later tests than students who practiced one type at a time.

Why does this work? Interleaving forces your brain to continually retrieve the correct strategy for each problem, rather than mindlessly applying the same approach. It feels harder and slower, but the difficulty is what makes it effective.

Mix problem types in your practice. If you're learning math, don't do 20 multiplication problems, then 20 division problems. Mix them together: a multiplication, then a division, then a fraction, then back to multiplication.

Alternate between subjects. Instead of studying history for three hours, then biology for three hours, try alternating: an hour of history, an hour of biology, an hour of history, and so on.

Embrace the difficulty. Interleaving will feel less productive than blocked practice. You'll make more errors and feel less fluent. That's the point. The struggle is what builds stronger memories.

For more ideas on effective studying, see my Best Study Skills page.

Part 4: Manage Your Mindset

If you're not careful, you can be your own worst enemy when it comes to remembering things. The power of positive thinking is real, and so is the power of negative thinking. If you tell yourself you have a bad memory, that belief can become self-fulfilling.

Research shows that stress and anxiety can interfere with memory formation and retrieval. When you're anxious about remembering something, that anxiety itself can block your recall. Confidence and calm help create the conditions where memory works best.[14]

Reframe "forgetting" as normal. Everyone forgets things. It doesn't mean your brain is broken. When you forget something, treat it as feedback: maybe you didn't encode it deeply enough, or maybe you need another spaced review. Forgetting is part of the learning process, not evidence of failure.

Prepare thoroughly so confidence is earned. The best antidote to test anxiety is genuine preparation. When you've used the techniques on this page (active recall, spaced repetition, interleaving), you'll know you've done the work. That knowledge builds real confidence.

Practice relaxation before high-stakes situations. If you're about to take a test, take a few minutes to calm your nervous system. Deep belly breathing works well. So does progressive muscle relaxation. Going into a recall situation calm rather than frantic gives your memory space to work.

Part 5: Lifestyle Factors That Support Memory

The strategies above are things you can do right now. But memory doesn't exist in a vacuum. These lifestyle factors create the foundation that makes everything else work better.

Get enough sleep. Sleep plays a critical role in memory consolidation. During sleep, your brain processes and strengthens the memories you formed during the day. Cutting sleep short actively interferes with this process.[15]

Most adults need 7-9 hours per night. If you're studying for something important, resist the temptation to sacrifice sleep for extra study time. A well-rested brain outperforms a sleep-deprived one, even if the sleep-deprived person studied longer.

Exercise regularly. We mentioned exercise earlier as a quick focus booster, but its long-term effects are even more impressive. Regular aerobic exercise increases the size of the hippocampus (the brain region most associated with memory) and promotes the growth of new neurons.[16]

You don't need to run marathons. Brisk walking, swimming, cycling: any activity that gets your heart rate up for 30 minutes, several times a week, can make a measurable difference.

Try meditation or mindfulness. Research suggests that meditation helps improve focus, concentration, and memory. Even a few minutes of mindful breathing can clear your mind and improve your ability to learn.[17]

Start with 5 minutes a day of simply focusing on your breath. When your mind wanders (it will), gently bring it back. This practice strengthens the same attention muscles you need for "Original Awareness."

Stay socially engaged. Studies suggest that maintaining close connections with friends and family helps preserve cognitive abilities. Social interaction exercises the brain in ways that solitary activities don't. Loneliness and social isolation are associated with faster cognitive decline.[18]

Keep learning new things. A 2023 study found that older adults learning multiple new real-world skills showed significant improvement in cognitive ability, including memory. Challenging your brain with genuine novelty keeps it sharp. Learn a new language, pick up a musical instrument, take up a craft. The key is novelty and challenge.[19]

Get into nature. A 2024 study found that walking in nature allowed the brain to rest and recover more than walking in an urban environment. Even exposure to indoor plants may boost working memory. Nature seems to give our brains a restorative break that supports cognitive function.[20][21]

To take memory improvement even further, explore the other areas of this site. The How to Get a Better Memory page is a good place to start.

References & Research

I've read these sources and selected them for their relevance to practical memory improvement. Here's what each contributes:

1. Kandola, A., Hendrikse, J., Lucassen, P.J., & Yücel, M. (2016). "Aerobic Exercise as a Tool to Improve Hippocampal Plasticity and Function in Humans: Practical Implications for Mental Health Treatment." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 373. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This comprehensive review examines how aerobic exercise affects hippocampal structure and function in humans. The evidence that exercise improves memory and cognitive function is strong and consistent across many studies. The hippocampus, critical for memory formation, actually grows in response to regular exercise.

2. Hsieh, L.T., & Ranganath, C. (2014). "Frontal midline theta oscillations during working memory maintenance and episodic encoding and retrieval." NeuroImage, 85(Pt 2), 721-729. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This review synthesizes evidence that theta oscillations (4-8 Hz) in the frontal midline region are associated with working memory and episodic memory. Controlled breathing and meditation have been shown to modulate theta activity, providing a plausible mechanism for how relaxation practices might support memory.

3. Richland, L.E., Kornell, N., & Kao, L.S. (2009). "The pretesting effect: Do unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance learning?" Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 15(3), 243-257. Free PDF from authors

Researcher's Note: This is the key study on the "pretesting effect." It's counterintuitive but well-replicated: attempting to answer questions before you know the material improves subsequent learning, even when you fail the pretest. The attempt primes your brain for encoding.

4. Rosner, Z.A., Elman, J.A., & Shimamura, A.P. (2013). "The generation effect: Activating broad neural circuits during memory encoding." Cortex, 49(7), 1901-1909. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This neuroimaging study shows that generating information (rather than passively reading) activates broader brain networks during encoding. The "generation effect" is well-established: producing answers yourself leads to better memory than simply reading them. The takeaway: don't just read. Make yourself produce the answer.

5. Mueller, P.A., & Oppenheimer, D.M. (2014). "The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking." Psychological Science, 25(6), 1159-1168. Free PDF

Researcher's Note: This study sparked debate (some replications have been mixed), but the core insight holds: writing by hand forces you to summarize and process rather than transcribe verbatim. The principle of active engagement remains sound even if the effect size is debated.

6. Hannon, B., Lozano, G., Farias, S., Hernandez, S., & Vasquez, V. (2014). "Differential-associative processing or example elaboration: Which strategy is best for learning the definitions of related and unrelated concepts?" Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28(1), 1-10. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This research examines elaborative strategies for learning, including elaborative interrogation (asking "why" and "how" questions). The study confirms that actively questioning material creates stronger memory traces than passive reading. Generating your own examples and explanations forces deeper processing.

7. Clark, J.M., & Paivio, A. (1991). "Dual coding theory and education." Educational Psychology Review, 3(3), 149-210. Free PDF at CSU Chico

Researcher's Note: This paper applies Paivio's dual coding theory to educational settings. Verbal and visual information are processed through separate channels; engaging both creates redundant memory traces. This is why combining words and images is more effective than either alone, and why visualization techniques are so powerful.

8. Miller, G.A. (1956). "The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information." Psychological Review, 63(2), 81-97. Free PDF

Researcher's Note: This classic paper established the concept of working memory limits. While the exact number has been debated (some argue it's closer to 4), the principle that chunking helps us work within our limits remains well-supported.

9. Roediger, H.L., & Karpicke, J.D. (2006). "The Power of Testing Memory: Basic Research and Implications for Educational Practice." Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(3), 181-210. Free PDF from authors

Researcher's Note: This is the landmark paper that put "active recall" on the map. It demonstrates that testing yourself is dramatically more effective than re-reading, even when you feel like re-reading is working better. This counterintuitive finding has transformed how I approach learning.

10. Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology. Translated 1913. psychclassics.yorku.ca/Ebbinghaus/

Researcher's Note: This is the foundational text for understanding how we forget. Ebbinghaus's "forgetting curve" has been replicated countless times over 140 years. If you only understand one concept from memory science, it should be this one.

11. Cepeda, N.J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J.T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). "Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis." Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354-380. Free PDF

Researcher's Note: This meta-analysis (a study of studies) confirms that spacing out your learning beats cramming across dozens of experiments. I consider this one of the most actionable findings in memory research.

12. Smolen, P., Zhang, Y., & Byrne, J.H. (2016). "The right time to learn: mechanisms and optimization of spaced learning." Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(2), 77-88. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This paper digs into the neuroscience behind why spaced repetition works at the cellular level. It shows this isn't just a behavioral trick. There are real biological mechanisms involving protein synthesis and synaptic consolidation.

13. Samani, J., & Pan, S.C. (2021). "Interleaved practice enhances memory and problem-solving ability in undergraduate physics." npj Science of Learning, 6, 32. doi.org/10.1038/s41539-021-00110-x

Researcher's Note: This study found that physics students who practiced with interleaved problem types showed 50-125% improvement on tests compared to blocked practice. The students themselves rated interleaving as "more difficult" and incorrectly believed they learned less from it. The difficulty is the point.

14. Kuhlmann, S., Piel, M., & Wolf, O.T. (2005). "Impaired memory retrieval after psychosocial stress in healthy young men." Journal of Neuroscience, 25(11), 2977-2982. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This study demonstrated that stress hormones actively impair memory retrieval. Test anxiety isn't just subjectively unpleasant; it physiologically interferes with your ability to recall information. Staying calm isn't just feel-good advice.

15. Rasch, B., & Born, J. (2013). "About Sleep's Role in Memory." Physiological Reviews, 93(2), 681-766. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This comprehensive review synthesizes decades of research on how sleep consolidates memory. The evidence is overwhelming: sleep isn't just rest for the body. It's an active process where the brain reorganizes and strengthens memories, particularly during slow-wave sleep.

16. Erickson, K.I., Voss, M.W., Prakash, R.S., et al. (2011). "Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 3017-3022. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This landmark study showed that aerobic exercise actually increases the size of the hippocampus in older adults. The hippocampus typically shrinks with age, contributing to memory decline. Exercise reverses this shrinkage and improves memory function.

17. Gothe, N.P., Khan, I., Hayes, J., Erlenbach, E., & Damoiseaux, J.S. (2019). "Yoga Effects on Brain Health: A Systematic Review of the Current Literature." Brain Plasticity, 5(1), 105-122. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This systematic review examines meditation and yoga's effects on cognition. The evidence is promising but still developing. I recommend meditation primarily because it's low-risk and may help with focus and stress reduction.

18. Ybarra, O., & Winkielman, P. (2012). "On-line social interactions and executive functions." Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 75. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This research showed that engaging in real-time social interaction improves performance on executive function tests. Social engagement exercises working memory, attention, and cognitive control in ways that make it a form of mental exercise.

19. Leanos, S., Kürüm, E., Strickland-Hughes, C.M., et al. (2023). "The Impact of Learning Multiple Real-World Skills on Cognitive Abilities and Functional Independence in Healthy Older Adults." The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 78(8), 1305-1317. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This study found that older adults who learned multiple new skills simultaneously (Spanish, drawing, music composition) showed cognitive improvements similar to people 30 years younger. It suggests that challenging your brain with genuine novelty produces real benefits.

20. McDonnell, A.S., & Strayer, D.L. (2024). "Immersion in nature enhances neural indices of executive attention." Scientific Reports, 14, 1845. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52205-1

Researcher's Note: This 2024 study using EEG found that walking in nature produced different brain activity patterns than walking in urban environments. Nature walks appeared to allow the brain to rest and recover more effectively.

21. Rhee, J.H., Schermer, B., Han, G., Park, S.Y., & Lee, K.H. (2023). "Effects of nature on restorative and cognitive benefits in indoor environment." Scientific Reports, 13, 13199. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40408-x

Researcher's Note: This 2023 study found that participants performed better on working memory tasks when plants were visible in the room. The effect size was modest, but it suggests even small nature exposure may have cognitive benefits.

22. Pearson, J., Naselaris, T., Holmes, E.A., & Kosslyn, S.M. (2015). "Mental Imagery: Functional Mechanisms and Clinical Applications." Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(10), 590-602. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This comprehensive review shows that visual mental imagery is a depictive internal representation that functions like a weak form of perception. Brain imaging confirms that when you vividly imagine something, similar neural patterns emerge as when you actually see it. This explains why visualization is such a powerful memory tool: you're essentially giving your brain a second "exposure" to the material.

Published: 02/07/2007

Last Updated: 12/21/2025

Newest / Popular

Multiplayer

Board Games

Card & Tile

Concentration

Math / Memory

Puzzles A-M

Puzzles N-Z

Time Mgmt

Word Games

- Retro Flash -

Also:

Bubble Pop

• Solitaire

• Tetris

Checkers

• Mahjong Tiles

•Typing

No sign-up or log-in needed. Just go to a game page and start playing! ![]()

Free Printable Puzzles:

Sudoku • Crosswords • Word Search

Hippocampus? Working memory? Spaced repetition?

Look up memory or brain terms in the A-Z glossary of definitions.