How Memory Works: The Science Behind Remembering

Here's something that surprised me when I first learned it: your memory isn't a filing cabinet. It's not even a single system. What we casually call "memory" is actually a set of interconnected processes that encode information, store it, and retrieve it later. Each stage works differently, fails differently, and can be improved differently.

Understanding how these processes work isn't just academic. It explains why you can remember your childhood phone number but not where you put your keys ten minutes ago. It reveals why cramming for exams feels productive but doesn't work. And it shows why certain memory techniques are so effective while others are a waste of time.

This page covers what neuroscience has learned about memory formation, the brain structures involved, the different types of memory, and why we forget. More importantly, it connects that science to practical strategies you can use. If you understand how memory works, you'll understand why the techniques on this site work.

The Three Stages of Memory

Every memory you've ever formed passed through three stages: encoding, storage, and retrieval. Psychologists Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin formalized this model in 1968, and while our understanding has grown more nuanced since then, the basic framework remains foundational.[1]

Encoding is the process of converting sensory information into a form your brain can store. When you meet someone new and hear their name, your brain must transform that auditory signal into a memory trace. How well you encode determines whether the memory forms at all. This is where attention matters most: if you weren't really paying attention when you heard the name, there's nothing to retrieve later. The failure wasn't forgetting. It was never properly encoding in the first place.

Storage is the maintenance of encoded information over time. Once a memory is formed, it must be kept in a state where it can be accessed later. This isn't passive. Your brain actively consolidates memories, particularly during sleep, strengthening some connections and letting others fade. Storage happens in different brain regions depending on the type of memory.

Retrieval is the process of accessing stored information when you need it. This is what most people think of as "remembering." But retrieval isn't like pulling a file from a cabinet. It's an active reconstruction, influenced by context, cues, and your current state. Many apparent memory failures are actually retrieval failures: the information is stored, but you can't access it in that moment.

Each stage offers opportunities for improvement. Memory techniques primarily enhance encoding by creating more durable memory traces. Learning strategies like spaced repetition optimize storage and retrieval. Brain health habits support the biological machinery that makes all three stages possible.

Encoding: How Memories Form

Not all encoding is equal. Craik and Lockhart's "levels of processing" framework, introduced in 1972, showed that the depth of mental processing during encoding predicts how well information will be remembered.[2]

Shallow processing involves surface features: what a word looks like, how it sounds. If I ask whether the word "TABLE" is written in capital letters, you're processing at a shallow level. This creates weak memory traces.

Deep processing involves meaning: what something signifies, how it relates to what you already know, what associations it triggers. If I ask whether "table" fits the sentence "The carpenter built a ___," you're processing at a deeper level. This creates stronger, more durable memories.

This is why passive reading is so ineffective for learning. When you read without engaging with the meaning, without asking questions or making connections, you're processing shallowly. The information passes through your brain without leaving much of a trace.

It's also why visualization techniques work so well. When you create a vivid mental image, you're forcing deep processing. You're engaging with meaning, making associations, and creating multiple pathways to the same information. The Memory Palace technique exploits this by linking new information to spatial memories you already have, creating a web of associations that makes retrieval almost automatic.

The Role of Attention

Encoding requires attention. This sounds obvious, but the implications are often missed. If your attention is divided, encoding suffers dramatically. Research consistently shows that trying to learn while multitasking produces significantly worse memory than focused attention.[3]

Memory expert Harry Lorayne called this "Original Awareness." His point: most forgetting isn't really forgetting. It's failure to form the memory in the first place because attention was elsewhere. When you "forget" where you put your keys, you probably weren't paying attention when you set them down. There was no memory to forget.

This is why the first step in any memory improvement effort is improving concentration. You can learn all the techniques in the world, but if you're not paying attention when information comes in, there's nothing to work with.

The Memory Systems: Short-Term, Working, and Long-Term

Your brain doesn't have just one memory system. Information moves through different systems with different characteristics, capacities, and brain locations.

Sensory Memory

Before information even reaches short-term memory, it passes through sensory memory. This is an extremely brief buffer (lasting milliseconds to a few seconds) that holds raw sensory impressions. Visual sensory memory (iconic memory) retains images for about a third of a second. Auditory sensory memory (echoic memory) lasts slightly longer, around 3-4 seconds.

Sensory memory is why you can "hear" the last few words someone said even if you weren't paying attention. That echoic trace lingers briefly, giving you a chance to process it. But if you don't attend to it quickly, it's gone.

Short-Term Memory

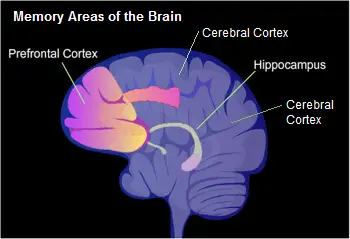

Information that receives attention moves into short-term memory. This is temporary storage lasting about 15-30 seconds without rehearsal. Short-term memory is located primarily in the hippocampus, the seahorse-shaped structure in the temporal lobe, along with a lesser-known structure called the subiculum.

The capacity of short-term memory is famously limited. In 1956, George Miller proposed the "magical number seven, plus or minus two" as the number of items short-term memory could hold. More recent research by Nelson Cowan has revised this downward. The actual capacity is closer to 3-5 chunks of information, not 7. The higher numbers Miller observed likely reflected chunking strategies that combined items into larger units.[4]

This limited capacity is why phone numbers are broken into chunks (555-867-5309 rather than 5558675309) and why you can't hold a dozen unrelated items in mind simultaneously. It's also why chunking is such an important memory strategy: by grouping information into meaningful units, you work within your capacity limits while remembering more total information.

Working Memory

Working memory is related to but distinct from short-term memory. While short-term memory is primarily about storage, working memory is about manipulation. It's your mental workspace where you hold information while actively thinking about it.

When you do mental arithmetic, following along with spoken directions, or hold the beginning of a sentence in mind while reading the end, you're using working memory. It's located primarily in the prefrontal cortex and is crucial for reasoning, comprehension, and learning.

Working memory capacity varies between individuals and correlates with general cognitive ability. Some researchers consider it the "bottleneck" of cognition: if you can't hold enough information in working memory simultaneously, complex thinking becomes difficult.

Long-Term Memory

Information that survives these temporary stages can be consolidated into long-term memory, where it can persist indefinitely. Long-term memory is distributed across the cerebral cortex, with different types of memory stored in different regions.

The capacity of long-term memory is, for practical purposes, unlimited. The problem isn't running out of storage space. The problem is getting information in effectively (encoding) and getting it back out when needed (retrieval).

Long-term memory isn't a single system. It's divided into several types, each with different characteristics and brain substrates.

Types of Long-Term Memory

The major division is between explicit (declarative) memory and implicit (non-declarative) memory.

Explicit Memory: What You Can Consciously Recall

Explicit memory is information you can consciously retrieve and describe. It's "knowing that" something is true. Endel Tulving famously divided explicit memory into two subtypes in 1972:[5]

Episodic memory stores personal experiences and events, complete with their spatial and temporal context. Your memory of your last birthday party, your first day at a new job, or what you had for dinner yesterday are all episodic memories. They're autobiographical, tied to a specific time and place in your life.

Episodic memory has a distinctive quality Tulving called "autonoetic consciousness": when you recall an episodic memory, you mentally travel back in time to the original experience. You don't just know that something happened; you remember experiencing it.

Semantic memory stores general knowledge and facts independent of when or where you learned them. Knowing that Paris is the capital of France, that water freezes at 32°F, or what a chair is: these are semantic memories. You can access this information without remembering the specific episode when you learned it.

The distinction matters because the two types of memory have different properties. Episodic memories are more fragile, more susceptible to forgetting and distortion. Semantic memories, once well-established, tend to be more stable. Interestingly, episodic memories can eventually become semantic: you might remember specific events where you learned about World War II, but over time, that knowledge becomes decontextualized semantic memory.

Implicit Memory: What You Know Without Knowing

Implicit memory is knowledge expressed through performance rather than conscious recollection. It's "knowing how" rather than "knowing that."

Procedural memory stores skills and how-to knowledge: riding a bike, typing on a keyboard, tying your shoes. You can't easily verbalize this knowledge, but you can demonstrate it through action. Procedural memories are stored primarily in the basal ganglia and cerebellum, separate from the hippocampal system that handles explicit memory.

This separation explains a striking finding from amnesia research. Patients with hippocampal damage who can't form new explicit memories can still learn new motor skills. They'll improve at a task over multiple sessions while having no conscious memory of ever practicing it.

Priming is another form of implicit memory: prior exposure to something influences your response to it later, even without conscious awareness. If you see the word "doctor," you'll recognize "nurse" faster afterward because related concepts are activated in your semantic network.

The Hippocampus: Memory's Critical Hub

The hippocampus deserves special attention because it's central to understanding how memory works. This small, curved structure in the temporal lobe is critical for converting short-term memories into long-term ones.

We know this largely from the famous case of H.M. (Henry Molaison), a patient who had his hippocampus removed in 1953 to treat severe epilepsy. After the surgery, H.M. could no longer form new explicit memories. He could remember his life before the surgery, could hold information in working memory, and could learn new motor skills. But he couldn't transfer new information into long-term declarative memory. Meeting him today, he would have no memory of meeting you yesterday.

The hippocampus acts as a kind of indexing system. Current research suggests that new memories are initially encoded in the hippocampus and then gradually consolidated into the neocortex over time, a process called systems consolidation. The hippocampus binds together the various elements of an experience (sights, sounds, emotions, context) into a coherent memory trace.[6]

This consolidation process happens largely during sleep, which is why sleep is so critical for memory. During deep sleep, the hippocampus replays recent experiences, strengthening important memories and transferring them to cortical storage. Cutting sleep short interrupts this process.

Why We Forget

Forgetting is often seen as a failure, but it's actually a feature of a well-functioning memory system. Research suggests that forgetting helps clear out irrelevant information, reduces interference between memories, and allows us to generalize from experience. A perfect memory that retained every detail would be overwhelmed with clutter.[7]

That said, we often forget things we'd rather remember. Understanding why helps identify solutions.

Encoding Failure

The most common reason for "forgetting" is that the memory was never properly formed. If you weren't paying attention, or if you processed information only shallowly, there's no memory to retrieve. This isn't really forgetting; it's never remembering in the first place.

Solution: Pay attention during encoding. Use deep processing strategies. Create meaningful associations.

Decay

Memories may weaken over time if not used. Memory traces are thought to be physical changes in neural connections, and these may fade without reinforcement. However, pure decay is difficult to demonstrate experimentally because you can't eliminate other factors during the passage of time.

Solution: Review important information at strategic intervals. Spaced repetition counteracts decay by strengthening memories before they fade.

Interference

Interference theory proposes that memories compete with each other. Proactive interference occurs when old memories interfere with retrieving new ones (your old phone number intruding when you try to recall your new one). Retroactive interference occurs when new memories interfere with old ones (learning someone's new name makes it harder to recall their old one).[8]

Interference is probably a bigger factor in everyday forgetting than pure decay. The more similar the competing memories, the greater the interference.

Solution: Make memories distinctive. The more unique and elaborately encoded a memory, the less vulnerable it is to interference. Space out the learning of similar material.

Retrieval Failure

Sometimes information is stored but temporarily inaccessible. The right retrieval cue can unlock it. This is the "tip of the tongue" phenomenon: you know you know something, but you can't quite access it. Later, a related thought suddenly brings it back.

Retrieval depends heavily on context. Memories encoded in a particular state (mood, location, even body position) are easier to retrieve in that same state. This is called "encoding specificity" or "context-dependent memory."

Solution: Create multiple retrieval cues during encoding. Connect new information to things you already know. Practice retrieval (testing yourself) to strengthen access pathways.

For a deeper exploration of why memories fail, see Why We Forget.

What This Means for Memory Improvement

Understanding how memory works has direct implications for improving it:

Encoding matters most. Most memory failures happen at the encoding stage. If you want to remember something, your primary job is to encode it well. Pay attention. Process deeply. Create associations. Make it meaningful. The visualization and association technique at the heart of most memory systems works because it forces deep, meaningful encoding.

Repetition isn't enough. Simply repeating information keeps it in short-term memory but doesn't guarantee long-term storage. Maintenance rehearsal (simple repetition) is less effective than elaborative rehearsal (thinking about meaning, making connections). And spacing out your repetition over time is dramatically more effective than massed practice.

Retrieval is practice for retrieval. Every time you successfully retrieve a memory, you strengthen it. Testing yourself is not just assessment; it's a powerful learning strategy. Active recall beats passive review because it exercises the retrieval pathways you'll need later.

Sleep isn't optional. Memory consolidation happens during sleep. If you're sleep-deprived, your brain can't properly convert short-term memories into long-term ones. Studying until 3 AM before an exam is counterproductive; you'd retain more by studying less and sleeping more.

The brain is biological. Memory depends on physical brain structures and processes. Brain health habits like exercise, nutrition, and stress management affect how well these systems function. You can't optimize software on failing hardware.

Putting It Together

Memory isn't magic, and it isn't fixed. It's a set of learnable processes that follow discoverable rules. The techniques that improve memory work because they align with how memory actually functions.

Memory techniques enhance encoding by creating vivid, meaningful, well-associated memory traces. Learning strategies optimize storage and retrieval through spaced practice and active recall. Brain health habits maintain the biological substrate that makes all of this possible.

For practical strategies you can start using today, see Quick Memory Tips. For an overview of the different memory systems and techniques, see Memory Skills. And for the lifestyle factors that support memory function, see Brain Health.

If you encounter unfamiliar terms, the Memory Glossary explains key concepts. For common misconceptions about memory, see Top 10 Memory Myths.

References & Research

I've reviewed these sources and selected them for their foundational importance to understanding how memory works. Here's what each contributes:

1. Atkinson, R.C., & Shiffrin, R.M. (1968). "Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes." In K.W. Spence & J.T. Spence (Eds.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation (Vol. 2, pp. 89-195). Academic Press. Free PDF from author's site

Researcher's Note: This is the foundational paper that established the multi-store model of memory. While subsequent research has refined our understanding (particularly of working memory), the basic framework of sensory input, short-term storage, and long-term memory remains central to how we think about memory systems. Every memory textbook builds on this work.

2. Craik, F.I.M., & Lockhart, R.S. (1972). "Levels of processing: A framework for memory research." Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671-684. ScienceDirect

Researcher's Note: This paper introduced the "levels of processing" framework that revolutionized how we think about encoding. The key insight that depth of processing predicts memory durability explains why active engagement beats passive reading. It's the scientific foundation for why memory techniques based on meaningful elaboration work so well.

3. Uncapher, M.R., & Wagner, A.D. (2018). "Minds and brains of media multitaskers: Current findings and future directions." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(40), 9889-9896. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This review examines the cognitive effects of media multitasking. The findings are sobering: heavy multitaskers show worse performance on tasks requiring sustained attention and memory. This supports the importance of focused attention during encoding and explains why studying while checking your phone undermines learning.

4. Cowan, N. (2010). "The Magical Mystery Four: How Is Working Memory Capacity Limited, and Why?" Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 51-57. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This paper updates our understanding of memory capacity limits. Miller's famous "seven plus or minus two" was more a rhetorical device than a precise measurement. Cowan's research shows the true capacity of working memory is closer to 3-5 chunks. This has practical implications for how we structure information when trying to learn it.

5. Tulving, E. (1972). "Episodic and semantic memory." In E. Tulving & W. Donaldson (Eds.), Organization of Memory (pp. 381-403). Academic Press. Free PDF

Researcher's Note: Tulving's distinction between episodic memory (personal experiences) and semantic memory (general knowledge) was foundational for memory research. Understanding that these are different systems with different properties helps explain why you might remember facts about an event but not experience remembering it, or vice versa.

6. Squire, L.R., Genzel, L., Wixted, J.T., & Morris, R.G. (2015). "Memory Consolidation." Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 7(8), a021766. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This comprehensive review covers the neuroscience of memory consolidation, including how memories transfer from hippocampus to cortex over time. It explains why sleep is so critical: consolidation happens largely during sleep, as the hippocampus replays and strengthens new memories. This is the science behind why sleep deprivation devastates learning.

7. Richards, B.A., & Frankland, P.W. (2017). "The Persistence and Transience of Memory." Neuron, 94(6), 1071-1084. Free full text at Cell

Researcher's Note: This paper presents a compelling argument that forgetting is a feature, not a bug. The authors propose that the goal of memory is not to transmit information perfectly but to optimize decision-making. Some forgetting helps by eliminating outdated information and allowing generalization. This reframes "forgetting" as sometimes adaptive rather than purely as failure.

8. Wixted, J.T. (2004). "The Psychology and Neuroscience of Forgetting." Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 235-269. ResearchGate

Researcher's Note: This review covers the major theories of forgetting, including decay, interference, and retrieval failure. Wixted argues that interference may be the primary cause of forgetting, not simple decay. Understanding interference helps explain why spacing out learning (reducing interference) is so effective and why similar material learned together can cause confusion.

Published: 03/16/2017

Last Updated: 12/28/2025

Newest / Popular

Multiplayer

Board Games

Card & Tile

Concentration

Math / Memory

Puzzles A-M

Puzzles N-Z

Time Mgmt

Word Games

- Retro Flash -

Also:

Bubble Pop

• Solitaire

• Tetris

Checkers

• Mahjong Tiles

•Typing

No sign-up or log-in needed. Just go to a game page and start playing! ![]()

Free Printable Puzzles:

Sudoku • Crosswords • Word Search

Hippocampus? Working memory? Spaced repetition?

Look up memory or brain terms in the A-Z glossary of definitions.