- Home

- Memory Skills

- Mnemonics

Mnemonics: Simple Memory Tricks That Actually Work

Some information just refuses to stick. The order of the planets. Which months have 31 days. The colors of the visible spectrum. You've encountered these facts dozens of times, yet when you need them, they slip away.

The problem isn't your memory. It's that these facts have nothing for your brain to grab onto. "Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars..." is just a list of names. There's no pattern, no story, no reason one comes before another. Your brain, which evolved to remember things that matter for survival, has no idea what to do with it.

Mnemonics solve this by giving abstract information a handle. "My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nachos" transforms a random sequence into something your brain already knows how to process: a sentence with meaning and rhythm. The planets haven't changed, but now you have a way to retrieve them.

These tricks have been around for centuries because they work. They're not the same as full memory systems like the Memory Palace, which can help you memorize vast amounts of information. Mnemonics are simpler, quicker, and more limited. But for the right kind of information, they're exactly what you need.

Why Mnemonics Work

Mnemonics aren't magic. They work because of how memory actually functions in the brain.

Your brain encodes information through multiple channels. Psychologist Allan Paivio's dual coding theory explains that we process verbal information (words) and visual information (images) through separate but connected systems. When you encode something through both channels, you create redundant memory traces. If one retrieval path fails, the other can still get you there.

This is why "ROY G. BIV" works better than trying to memorize "Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, and Violet" as a raw list. As you may know, those are the colors of the visible light spectrum, in order of decreasing wavelength.

But "ROY G. BIV" gives you a name (verbal), and you might picture a guy named Roy wearing a rainbow tie (visual). Two paths to the same information. The name "Roy" alone can act as a hook or clue that instantly reminds you of the ROY G. BIV mnemonic. The mnemonic, in turn, gives you the list.

Meaningful connections beat rote repetition. Your brain is a pattern-recognition machine. It excels at remembering things that connect to what you already know. Research consistently shows that elaborative encoding, where you create meaningful associations with new information, produces stronger memories than simple repetition.

When you learn "Kids Pour Catsup Over Fat Green Spiders" for taxonomy (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species), you're creating a bizarre image that links to familiar concepts: kids, catsup, spiders. Your brain already has robust memory networks for these things. The mnemonic piggybacks on them.

Structure provides retrieval cues. One reason lists are hard to remember is that there's nothing to prompt the next item. Once you forget "Mars," how do you get to "Jupiter"? Mnemonics impose structure: the next word in the sentence, the next letter in the acronym, the next line of the rhyme. Each element cues the next.

Types of Mnemonics

Most mnemonics fall into a few categories. Understanding these helps you both use existing mnemonics and create your own.

Acronyms

Acronyms take the first letter of each item and form them into a pronounceable word. They work best when the letters happen to spell something memorable.

ROY G. BIV for the visible light spectrum (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet) is the classic example. You get a name you can say aloud, which is easier to remember than seven separate color words.

HOMES for the Great Lakes (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior) works because it's an actual word with meaning. You can picture houses by a lake.

FANBOYS for coordinating conjunctions (For, And, Nor, But, Or, Yet, So) gives grammar students a single word instead of seven.

The limitation of acronyms is that the first letters of your list might not cooperate. If you need to remember tomatoes, zucchini, milk, green beans, and cereal, you get "TZMGC," which isn't a word and barely pronounceable. That's when you need a different approach.

Acrostics

Acrostics use the first letter of each item to create a sentence rather than a single word. This gives you much more flexibility, since any letter can start a word.

"My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nachos" (or "Nine Pizzas" if you still count Pluto) handles the planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune. The sentence is easy to remember because it tells a mini-story.

"Kids Pour Catsup Over Fat Green Spiders" covers biological taxonomy: Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species. The image is absurd, which makes it stick.

"Every Good Boy Does Fine" gives music students the notes on the treble clef lines (E, G, B, D, F). The spaces spell FACE, which is an acronym.

A reader named Robert from the UK shared his mnemonic for the light spectrum: "Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain." This refers to King Richard III's defeat by Henry Tudor. Same first letters as ROY G. BIV, but with a historical story attached. If history resonates with you more than a fictional character named Roy, use that version instead.

The point is that acrostics are flexible. If a standard mnemonic doesn't click for you, create your own sentence using the same first letters.

Rhymes and Songs

Rhyme and rhythm are powerful memory aids. There's a reason you can still sing songs you learned as a child but struggle to remember what you read yesterday. Music engages multiple brain systems and creates strong temporal patterns.

"Thirty days hath September, April, June, and November. All the rest have thirty-one, except February..." This rhyme has been helping people remember month lengths for centuries. The rhythm carries you through.

"I before E, except after C, or when sounding like A, as in neighbor and weigh." English spelling rules are notoriously irregular, but this rhyme captures a useful pattern. (It has exceptions, as English always does, but it's right often enough to help.)

The alphabet song is so effective that most English speakers can't recite the alphabet without hearing the tune in their heads. Try saying the letters without the melody. It's surprisingly difficult.

The downside of musical mnemonics is that they take effort to create. Unless someone has already made a song for what you need to learn, you probably won't compose one yourself. But if a good one exists, it's worth using.

Physical and Visual Mnemonics

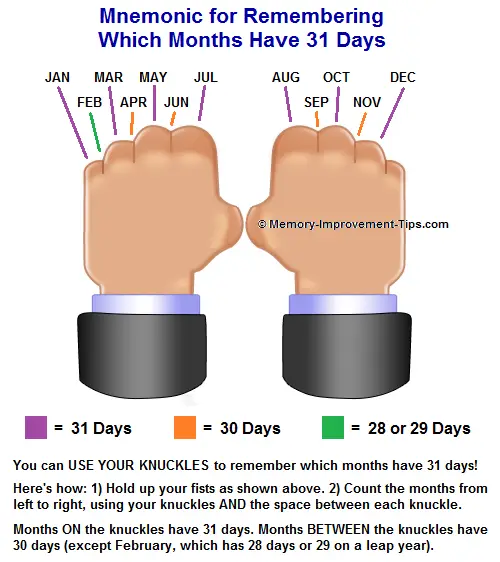

Your body can serve as a mnemonic device. The most useful example is the knuckle method for remembering which months have 31 days:

Make fists with both hands and look at your knuckles. Starting with your left pinky knuckle as January, count across: knuckles are months with 31 days, valleys between knuckles are shorter months. When you reach your left index knuckle (July), continue with your right index knuckle (August). Both July and August have 31 days, which is why two knuckles are adjacent.

This works because you always have your hands with you, and the pattern is consistent. Once you learn it, you'll never need to recite the rhyme again.

Another physical mnemonic: to remember which way to turn a screw, imagine turning a steering wheel. "Righty-tighty, lefty-loosey" maps to the hand motion you already know.

Chunking and Number Patterns

Strictly speaking, chunking is a broader memory strategy, but it often works as a simple mnemonic for numbers.

Phone numbers are designed this way. 5551234567 is hard to hold in mind, but 555-123-4567 breaks it into three manageable pieces. Your working memory can handle about four chunks at once, so three groups of digits fit comfortably.

Dates work similarly. 1776 is easier to remember if you notice it's 17-76, or that 7+7=14 and 1+6=7. Finding any pattern, even an arbitrary one, gives your brain a hook.

For more serious number memorization, the Major System and Memory Palace are far more powerful. But for a quick phone number or date, chunking and pattern-finding often suffice.

How to Create Your Own Mnemonics

Pre-made mnemonics exist for common material: planets, taxonomy, spelling rules, music notation. But you'll often encounter information that doesn't have a ready-made trick. Here's how to build your own.

Start with the first letters. Write down the first letter of each item you need to remember. Can you form them into a word (acronym) or a sentence (acrostic)? Play with the letters until something clicks.

Make it vivid and specific. "Big Elephants Can Always Understand Small Elephants" (for spelling BECAUSE) works better than a bland sentence because you can picture it. The more concrete and strange the image, the better it sticks.

Use what you already know. Connect new information to existing knowledge. If you're into sports, make a sports-themed sentence. If you love movies, reference characters you know well. Personal connections are stronger than generic ones.

Don't overthink it. A mnemonic only needs to work for you. It doesn't need to be clever or shareable. If "My Very Excellent Meatloaf Just Sat Under Newspapers" helps you remember the planets, use it, even if it makes no sense to anyone else.

Test yourself. Create the mnemonic, then look away and try to reconstruct the original information. If you can't, refine the mnemonic. Maybe the sentence isn't vivid enough, or the acronym is hard to pronounce. Adjust until retrieval feels easy.

When Mnemonics Work Best

Mnemonics are ideal for:

Fixed sequences. The planets always come in the same order. The taxonomy levels don't change. Mnemonics preserve order naturally.

Categorical lists. Items that share a category (Great Lakes, cranial nerves, coordinating conjunctions) often have first letters that can form patterns.

Rules and formulas. "SOH-CAH-TOA" for trigonometry ratios (Sine = Opposite/Hypotenuse, etc.) packages three formulas into one pronounceable chunk.

Spelling and grammar. English is full of irregular patterns. Mnemonics help you remember the exceptions.

When You Need More Than Mnemonics

Mnemonics have limits. They're shortcuts for specific, bounded information. For larger or more complex material, you'll need more powerful tools.

For memorizing long lists or large volumes of information, the Memory Palace (Method of Loci) is far more effective. Memory champions use it to memorize hundreds of items in order. Once you learn the technique, you can build multiple palaces for different subjects.

For connecting items in a narrative chain, the Link Method creates vivid stories that string information together. It's faster to learn than the Memory Palace and works well for medium-length lists.

For vocabulary and paired associations, the Keyword Method uses sound-alike words to create memorable images linking a word to its meaning.

For long-term retention, no encoding trick replaces spaced repetition. Mnemonics help you learn something initially, but without review at strategic intervals, even well-encoded memories fade. The combination of a good mnemonic plus spaced review is powerful.

Think of mnemonics as the right tool for quick jobs. They're the duct tape of memory: useful, versatile, and sometimes all you need. But if you're building something bigger, you'll want the full toolkit.

References

These sources inform the science behind why mnemonics work. I've selected them for accessibility and relevance to understanding memory encoding.

1. Paivio, A. (1991). "Dual coding theory: Retrospect and current status." Canadian Journal of Psychology, 45(3), 255-287. Full PDF on Sci Hub

Researcher's Note: Paivio's dual coding theory is foundational for understanding why visual and verbal mnemonics work. The core insight: information encoded through both verbal and visual channels creates redundant memory traces, improving recall. This explains why "ROY G. BIV" (a name you can picture) beats memorizing the color list directly.

2. Craik, F.I.M., & Lockhart, R.S. (1972). "Levels of processing: A framework for memory research." Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671-684. Free PDF at UC San Diego

Researcher's Note: This classic paper introduced the "levels of processing" framework. Deeper, more meaningful processing (like creating associations) produces stronger memories than shallow processing (like rote repetition). Mnemonics work precisely because they force you to process information meaningfully.

3. Dresler, M., Shirer, W.R., Konrad, B.N., et al. (2017). "Mnemonic Training Reshapes Brain Networks to Support Superior Memory." Neuron, 93(5), 1227-1235. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This study compared memory athletes to controls and found that mnemonic training actually changes brain connectivity patterns. After just six weeks of training, ordinary people showed brain network changes resembling those of memory champions. The effects lasted at least four months after training ended.

4. Hampstead, B.M., Sathian, K., Phillips, P.A., et al. (2012). "Mnemonic strategy training improves memory for object location associations in both healthy elderly and patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a randomized, single-blind study.". Neuropsychology, 26(3), 385-399. Free full text at PMC

Researcher's Note: This randomized controlled trial compared mnemonic strategy training against simple repeated exposure. The mnemonic group used mental imagery, linking objects to salient features with verbal reasons. Results: mnemonic strategies significantly outperformed exposure alone, with benefits persisting at least one month after training. The study demonstrates that actively creating meaningful associations beats passive repetition.

5. Clark, J.M., & Paivio, A. (1991). "Dual coding theory and education." Educational Psychology Review, 3(3), 149-210. Free PDF at CSU Chico

Researcher's Note: This paper applies dual coding theory specifically to educational settings. The authors demonstrate how combining verbal instruction with visual materials consistently improves learning outcomes. The implications for mnemonics are clear: the best memory tricks engage both verbal and visual systems.

Published: 02/07/2007

Last Updated: 01/23/2026

Newest / Popular

Multiplayer

Board Games

Card & Tile

Concentration

Math / Memory

Puzzles A-M

Puzzles N-Z

Time Mgmt

Word Games

- Retro Flash -

Also:

Bubble Pop

• Solitaire

• Tetris

Checkers

• Mahjong Tiles

•Typing

No sign-up or log-in needed. Just go to a game page and start playing! ![]()

Free Printable Puzzles:

Sudoku • Crosswords • Word Search

Hippocampus? Working memory? Spaced repetition?

Look up memory or brain terms in the A-Z glossary of definitions.