- Home

- Remembering Numbers

The Major System: How to Remember Any Number

Memory competitors routinely memorize hundreds of random digits in minutes. One Japanese mental athlete, Akira Haraguchi, has recited over 100,000 digits of pi. These aren't savants with superhuman brains. They're using a technique you can learn in an afternoon.

The Major System (also called the Phonetic Number System or Phonetic Mnemonic System) converts numbers into consonant sounds, which you then turn into words. Since words are infinitely easier to remember than digit strings, the problem of memorizing numbers becomes the much simpler problem of remembering a few vivid images.

The technique has been refined over 300 years. Today it remains the foundation of competitive memory sports and a practical tool for anyone who needs to remember PINs, passcodes, dates, phone extensions, or any other numerical information.

Why Numbers Are So Hard to Remember

Numbers are abstract. The digit "7" doesn't look like anything, sound like anything, or connect to anything in your experience. Your brain has nothing to grab onto.

Compare that to the phrase "Four score and seven years ago." That's 30 characters in a specific order, yet most Americans can recall it perfectly. Now try memorizing the 30-digit number "856713543887543652367836912." Same length, but essentially impossible through brute repetition.

The difference is chunking. Letters form words, and words form meaningful phrases. Your brain encodes "Four score and seven" as a single unit linked to Lincoln and the Civil War. It's rich with associations. The number string has none.

The Major System solves this by giving you a way to convert any number into words. Once a number becomes a word or phrase, you can visualize it, connect it to things you know, and remember it like any other information.

A Brief History

The earliest version of this technique appeared in 1634 when French mathematician Pierre Hérigone published a system linking numbers to letters. Over the next two centuries, various scholars refined it. In 1825, Aimé Paris published what is essentially the modern form.

The name "Major System" likely comes from a 19th-century memory instructor named Major Beniowski, though some argue the name simply reflects that it's the "major" (primary) system for memorizing numbers.

In the 20th century, memory expert Harry Lorayne popularized the technique through his bestselling books, including The Memory Book (1974, co-authored with basketball star Jerry Lucas). Today, nearly every competitive memorizer uses some version of this system.

The Number-to-Sound Code

The Major System assigns consonant sounds to each digit from 0-9. Vowels (a, e, i, o, u) have no numerical value and can be inserted freely to create words. The consonants W, H, and Y are also "free" and carry no value.

Here's the code:

| Digit | Sound(s) | Memory Aid |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | s, z, soft c | Zero starts with Z |

| 1 | t, d, th | A typed "t" or "d" has 1 downstroke |

| 2 | n | A typed "n" has 2 downstrokes |

| 3 | m | A typed "m" has 3 downstrokes |

| 4 | r | Four ends with R |

| 5 | l | Hold out your left hand: 5 fingers form an "L" |

| 6 | j, ch, sh, soft g | A "J" looks like a reversed 6 |

| 7 | k, hard g, hard c, q | Two 7s back-to-back form a "K" |

| 8 | f, v | A handwritten "f" looks like an 8 |

| 9 | p, b | A "9" is a mirrored "p" or flipped "b" |

Critical point: The system is phonetic, based on sounds rather than spelling. The word "ghost" encodes as 701 (g-silent h-o-s-t = hard g, s, t = 7-0-1), not 7501. Double letters count once: "butter" is 914 (b-u-tt-e-r = b, t, r = 9-1-4), not 9114.

Notice that letters sharing similar mouth positions are grouped together. The sounds "t" and "d" both involve the tongue touching the roof of your mouth. The sounds "p" and "b" both involve your lips popping. This makes the system easier to learn than it first appears.

Sounds That Are "Free"

Vowels (a, e, i, o, u) carry no numerical value. Neither do the consonants W, H, and Y. You can insert these freely to create words from your consonant sounds. This flexibility is what makes the system powerful.

For example, the number 21 (n-t) could become: net, nut, knot, note, night, neat, hunt, haunt, or ante. All of these words have exactly the sounds n and t in that order, with free letters filling the gaps.

How to Use the Major System

The process has three steps:

Step 1: Convert the number to consonant sounds. Break the number into chunks of 2-3 digits and identify the consonant sounds for each chunk.

Step 2: Form words from those sounds. Add vowels and free consonants to create memorable words. Concrete nouns work best because they're easy to visualize.

Step 3: Create a vivid mental image. Use visualization and association to link your word(s) to whatever context you need (a location, a person, another piece of information).

Let me walk through two practical examples.

Example 1: Remembering a 6-Digit Passcode

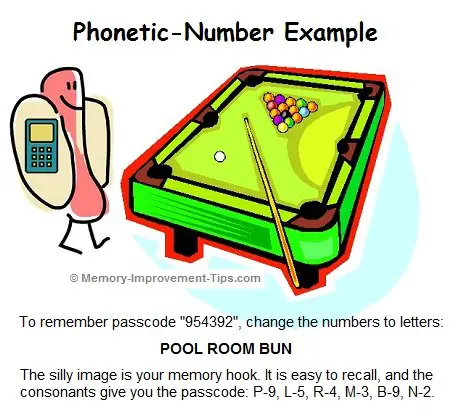

Your workplace assigns you a new door code: 954392. You're not allowed to write it down. How do you lock it into memory?

First, convert to sounds:

9 = p/b 5 = l 4 = r 3 = m 9 = p/b 2 = n

Now form words. You could split this as 954-392 (p-l-r and m-p-n), but that's awkward. Try 95-43-92: p-l, r-m, p-n. That gives you potential words like: pool (95), room (43), bun (92).

POOL ROOM BUN

Now create a vivid image. Picture a giant hotdog in a fluffy bun playing billiards in a smoky pool hall. The hotdog is wearing sunglasses and chalking its cue. Really see this scene.

Associate this image with the door at work. Maybe the keypad buttons are tiny hotdog buns. When you approach the door, the image pops into your head: hotdog bun playing pool → POOL ROOM BUN → 954392.

Silly? Absolutely. Effective? Extremely. The silliness is the point. Research confirms that distinctive, unusual images are recalled better than ordinary ones.[3]

Example 2: Memorizing Sales Figures for a Presentation

You're presenting quarterly sales to your company's leadership: Widget A sold $53,000, Widget B sold $82,000, Widget C sold $19,000. You want to deliver these figures confidently without glancing at notes.

The challenge here is remembering which figure goes with which widget. We'll combine the Major System with an Alphabet Peg (A = Hay, B = Bee, C = Sea) to keep everything organized.

Since all amounts are rounded to thousands, we only need to encode 53, 82, and 19:

53 = l, m → LAME

82 = f, n → FAN

19 = t, p → TAPE

Now link each to its letter peg:

A (Hay) + LAME: Picture a giant haystack hobbling down the road with a cane, limping badly. It's a lame haystack. When you think "Widget A," you see the limping hay → LAME → 53 → $53,000.

B (Bee) + FAN: Picture a swarm of bees flying into a spinning fan. Chaos ensues. Widget B → bees + fan → FAN → 82 → $82,000.

C (Sea) + TAPE: Picture silver duct tape stretched across the ocean waves, trying to hold the sea together. Widget C → sea + tape → TAPE → 19 → $19,000.

Now there's no way to confuse which figure belongs to which widget. Each is anchored to a distinct, memorable image.

Building a Permanent Number Vocabulary

With practice, you can pre-memorize images for every two-digit number from 00 to 99. This creates a mental vocabulary of 100 "peg" images you can deploy instantly.

For example:

00 = s-s → SAUCE or SASSY

01 = s-t → SUIT or SEED

02 = s-n → SUN or SWAN

...

47 = r-k → ROCK or RAKE

...

99 = p-p → PUPPY or POPE

With this vocabulary memorized, any long number becomes a sequence of images you can string together using the Link Method or place in a Memory Palace. This is exactly how memory competitors memorize hundreds of digits in minutes.

The Peg Systems page covers this approach in more detail.

Combining with the Memory Palace

The Major System and Memory Palace technique are natural partners. Once you've converted numbers into images, you can place those images along a mental route through a familiar location.

Want to memorize the first 20 digits of pi (3.14159265358979323846)? Convert chunks to images: 14 = TIRE, 15 = TOWEL, 92 = PAN, 65 = JAIL, 35 = MULE... then place each image at successive locations in your palace. Walk the route mentally, and the digits come back in order.

This combination scales remarkably well. Memory athletes use systems of several hundred or even a thousand pre-memorized images, placing them rapidly through vast mental architectures.

Alternative: The Dominic System

British memory champion Dominic O'Brien developed an alternative approach called the Dominic System. Instead of sounds, it maps numbers to letters directly (0=O, 1=A, 2=B... up to 9=N), then converts two-digit numbers into people's initials.

For example, 15 becomes AE, which might represent Albert Einstein. 37 becomes CG, perhaps Che Guevara. You then imagine these people performing actions at locations in your memory palace.

The Dominic System can be faster to learn initially since you're working with familiar people rather than abstract word conversions. However, the Major System is more flexible and widely used. Most serious competitors either use the Major System or hybrid approaches that combine elements of both.

When to Use Simpler Methods

The Major System is powerful but requires practice. For short numbers you only need temporarily, simpler approaches may be more practical.

Direct chunking works well for phone numbers and similar sequences. Breaking 8005551234 into 800-555-1234 and finding patterns (800 is a toll-free prefix, 555 is the fictional Hollywood exchange, 1234 is a sequence) requires no special training.

Rhymes and stories can encode specific numbers you use repeatedly. "In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue" is effectively a mini Major System application, using meaningful words to anchor an abstract date.

The Major System shines when you need to remember many numbers, longer sequences, or information you'll need to retrieve reliably over time. If you're a student memorizing historical dates, a professional tracking product codes, or anyone who regularly deals with numerical data, investing the time to learn this system pays dividends.

Why This Works: The Science

The Major System leverages several well-documented principles of memory.

Dual coding. Allan Paivio's dual coding theory explains that information processed through both verbal and visual channels creates redundant memory traces. When you convert "954392" to the image of a hotdog playing pool, you've encoded the number both as sounds (pool-room-bun) and as a picture. Either pathway can retrieve the memory.[1]

Chunking. George Miller's classic research established that working memory holds about seven items. By converting digits into words, you reduce six separate items (9-5-4-3-9-2) to three chunks (pool-room-bun). This fits comfortably within working memory's capacity.[2]

Distinctiveness. Research by McDaniel and Einstein found that unusual or bizarre images are recalled better than ordinary ones when they appear among common material. A hotdog playing pool stands out. Your brain flags it as noteworthy and encodes it more deeply.[3]

Elaboration. The process of creating an image forces you to engage deeply with the material. You're not passively repeating digits; you're actively constructing a vivid scene. This elaborative encoding creates stronger memory traces than rote repetition.

Getting Started

Here's a practical path to learning the Major System:

Week 1: Memorize the number-to-sound code. Use the memory aids in the table above. Quiz yourself until you can instantly convert any digit to its sounds and vice versa.

Week 2: Practice converting short numbers (2-4 digits) to words. Don't worry about speed; focus on finding words that create clear mental images. Use online Major System word generators if you get stuck.

Week 3: Start using the system for real information: phone extensions, PINs, dates. Each time you successfully recall a number using the system, you reinforce the habit.

Ongoing: Gradually build your vocabulary of pre-memorized images for 00-99. This takes time but dramatically increases your speed and capacity.

The system feels awkward at first. Converting numbers to words, then to images, then back again seems slow and cumbersome. But with practice, the conversions become automatic. Eventually you'll "see" images when you encounter numbers, without conscious effort.

That's when the real power emerges. Numbers that once slipped away become as memorable as faces, as sticky as stories. The ancient technique works as well today as it did three centuries ago.

Important: This page provides general educational information about memory techniques. For comprehensive guidance on using memory systems, see my Memory Skills overview. Questions about specific techniques? Check my Editorial Standards for how I research and verify information.

References & Research

I've reviewed these sources and selected them for their relevance to understanding why the Major System works. Here's what each contributes:

1. Clark, J.M., & Paivio, A. (1991). "Dual coding theory and education." Educational Psychology Review, 3(3), 149-210. Free PDF at CSU Chico

Researcher's Note: This paper applies Paivio's dual coding theory to educational settings. Verbal and visual information are processed through separate channels, and engaging both creates redundant memory traces. This explains the power of visualization in all mnemonic systems, including the Major System.

2. Miller, G.A. (1956). "The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information." Psychological Review, 63(2), 81-97. Free PDF at Max Planck

Researcher's Note: Miller's landmark paper established that working memory has limited capacity, roughly seven items. This explains why raw digit strings are so hard to remember and why chunking (grouping items into larger units) is so effective. The Major System exploits chunking by converting multiple digits into single words.

3. McDaniel, M.A., & Einstein, G.O. (1986). "Bizarre imagery as an effective memory aid: The importance of distinctiveness." Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 12(1), 54-65. Full text on ResearchGate

Researcher's Note: This research clarified when and why bizarre images help memory. The effect is strongest when unusual images appear among common material, which is exactly how the Major System works: your vivid hotdog-playing-pool image stands out against the ordinary context of your workplace door. Distinctiveness drives recall.

4. Higbee, K.L. (1976). "Mnemonic Systems in Memory: Are They Worth the Effort?" Paper presented at the Rocky Mountain Psychological Association Meeting. ERIC

Researcher's Note: Higbee (author of Your Memory: How It Works and How to Improve It) reviewed research on four major mnemonic systems, including the phonetic system. His conclusion: mnemonic systems make enough contribution to memory to warrant their mastery. The phonetic system, while the most complex to learn, offers the most flexibility for number memorization.

5. Yates, F.A. (1966). The Art of Memory. University of Chicago Press. Publisher

Researcher's Note: The definitive scholarly history of memory techniques from antiquity through the Renaissance. While the Major System itself emerged later, Yates documents the deep tradition of converting abstract information into memorable images. The techniques memory champions use today have roots stretching back over two millennia.

6. Lorayne, H., & Lucas, J. (1974). The Memory Book: The Classic Guide to Improving Your Memory at Work, at School, and at Play. Ballantine Books.

Researcher's Note: Harry Lorayne popularized the Major System for general audiences through this bestseller and his many other books. His clear explanations and practical examples made these techniques accessible to millions. Much of the terminology I use on this site comes from Lorayne's work. If you want to go deeper, his books remain excellent practical guides.

Published: 04/01/2008

Last Updated: 01/16/2026

Newest / Popular

Multiplayer

Board Games

Card & Tile

Concentration

Math / Memory

Puzzles A-M

Puzzles N-Z

Time Mgmt

Word Games

- Retro Flash -

Also:

Bubble Pop

• Solitaire

• Tetris

Checkers

• Mahjong Tiles

•Typing

No sign-up or log-in needed. Just go to a game page and start playing! ![]()

Free Printable Puzzles:

Sudoku • Crosswords • Word Search

Hippocampus? Working memory? Spaced repetition?

Look up memory or brain terms in the A-Z glossary of definitions.