- Home

- Memory Skills

- Learning Strategies

- Spaced Repetition

Spaced Repetition: Why It Beats Cramming

If you've ever crammed for a test, aced it, and then forgotten everything a week later, you've experienced why spaced repetition matters. The information was in your head, but it didn't stick.

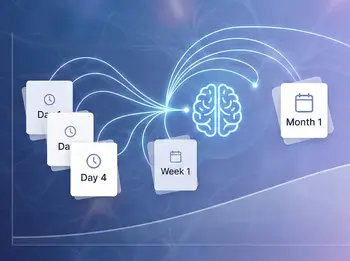

Spaced repetition fixes this. Instead of cramming everything into one marathon session, you spread your reviews over time: today, then tomorrow, then in a few days, then a week. Each review happens just before you'd forget, and each one makes the memory stronger.

The results are dramatic. Meta-analyses consistently show that spacing produces 200% better retention than massed practice (cramming), sometimes more. A 2021 meta-analysis found a strong effect size of 0.74 for spaced retrieval practice. In practical terms, that's the difference between forgetting most of what you studied and actually remembering it months later.

This page covers why spacing works, how to calculate optimal review intervals, the tools you can use (from index cards to apps), and how to actually make this work in your life.

The Forgetting Curve (And How to Beat It)

Back in 1885, a German psychologist named Hermann Ebbinghaus ran a grueling experiment on himself. He memorized lists of nonsense syllables (things like "DAX" and "BUP") and then tested how quickly he forgot them.

What he found was sobering: without review, we lose roughly 50-80% of new information within days. The steepest drop happens in the first few hours. This pattern, the forgetting curve, has been replicated countless times since.

But Ebbinghaus discovered something more useful. Each time you successfully recall information before it's completely gone, you slow down the forgetting. The curve still slopes downward, but less steeply. Review again at the right moment, and it flattens further. After enough well-timed reviews, information that would have vanished in days can last for years.

This is the core insight behind spaced repetition: time your reviews to catch memories just as they're starting to fade. You're essentially re-strengthening the memory at the moment when that strengthening does the most good.

How Long Should You Wait Between Reviews?

This turns out to depend on how long you need to remember the material. There's no single "best" spacing interval; it shifts based on your goal.

Researchers tested this systematically in a study with over 1,350 participants. People learned a set of facts, reviewed them after gaps ranging from zero to 3.5 months, and then were tested at delays up to one year.

The findings give us practical guidance:

For a test in one week, the sweet spot for your review gap is about 1-2 days after initial learning.

For a test in one month, you want to wait about a week before reviewing.

For retention over one year, your first review should be roughly 3-4 weeks out.

The researchers found a rough rule of thumb: the optimal gap is about 10-20% of the time you need to remember something. If you need the information for a year, wait a few weeks before your first review. If you just need it for next week's exam, review after a day or two.

Reviewing too soon wastes effort because the memory is still strong. Reviewing too late means you've forgotten too much and have to relearn rather than reinforce. The sweet spot is in between.

Why Harder Retrieval Means Stronger Memory

Here's something that trips people up: the strategies that feel easiest during studying often produce the weakest retention.

When you space out your practice, recalling the material is harder because you've partially forgotten it. That difficulty feels like failure. But research by Robert and Elizabeth Bjork shows that this struggle is actually beneficial. They call it "desirable difficulty." When your brain has to work harder to retrieve a memory, that effortful retrieval strengthens the memory more than easy recall does.

This explains why cramming feels so productive. Right after a study session, recall is easy. You feel like you know the material. But that fluent recall is a trap. Because retrieval was effortless, it didn't do much to strengthen the memory. A week later, it's gone.

Spaced practice feels less effective in the moment precisely because it's more effective for the long term.

Spacing Systems You Can Actually Use

You don't need fancy software to use spaced repetition. People have been doing this with index cards for decades. That said, software does make it easier, especially if you're dealing with hundreds or thousands of items.

The Leitner Box System

In 1972, German science journalist Sebastian Leitner published a book called "How to Learn to Learn," introducing a simple system using flashcards and a few boxes.

Here's how it works: You set up three to five boxes, each representing a different review interval. All new cards start in Box 1. When you get a card right, it moves to the next box. When you get it wrong, it goes back to Box 1 (or moves back one box, depending on the variation you use).

Box 1 gets reviewed every day. Box 2 every other day. Box 3 once a week. Box 4 every two weeks. Box 5 monthly.

Cards you struggle with keep cycling through the frequent-review boxes. Cards you know well gradually move toward boxes with longer intervals. The system automatically focuses your time on what you haven't mastered yet.

For physical implementation, you can use actual boxes, envelopes, or even just rubber bands to keep card groups separate. It works well for a few hundred cards. Beyond that, managing the logistics gets cumbersome.

Software: Anki and Friends

For larger collections or more precise scheduling, software takes over the bookkeeping. The most popular option is Anki, a free, open-source program that runs on computers, phones, and the web.

Anki tracks every card you study. When you review, you rate your recall (Again, Hard, Good, or Easy), and the algorithm calculates when to show you that card again. Cards you struggle with appear soon. Cards you nail get scheduled further out. Over time, the system adapts to your learning patterns.

The algorithm is based on work by Piotr Woźniak, who developed the original SuperMemo software in Poland starting in 1985. His SM-2 algorithm, published in 1987, is still the foundation for Anki and many other spaced repetition programs.

Anki's other big advantage is its library of shared decks. Users have created flashcard sets for languages, medical school, law, programming, history, and nearly anything else. You can also make your own cards, which some research suggests is more effective because creating forces you to process the material.

Other options include SuperMemo (the original, still actively developed), Mnemosyne (simpler than Anki), Quizlet (popular with students, though its spacing features are more limited), and RemNote (combines notes with flashcards).

The Pimsleur Method for Languages

If you've used Pimsleur language courses, you've experienced spaced repetition built into audio lessons. Paul Pimsleur, a professor of applied linguistics, developed his "graduated interval recall" system in 1967.

His original schedule called for reviews at 5 seconds, 25 seconds, 2 minutes, 10 minutes, 1 hour, 5 hours, 1 day, 5 days, 25 days, 4 months, and 2 years. The Pimsleur courses build these intervals into the lesson structure, so you get spaced review automatically just by following along.

While later research refined our understanding of optimal intervals, Pimsleur was right about the core principle: when you review matters as much as what you review.

Making Spaced Repetition Work

Getting started is easy. Making it stick requires a few practical considerations.

Start Smaller Than You Think

The most common way people fail with spaced repetition is adding too many cards too fast. Every card you add today becomes a review you'll owe tomorrow, next week, and next month. Add 50 new cards daily and you'll soon face 200+ daily reviews. That's not sustainable for most people.

Start with 10-20 new cards per day, maximum. You can always increase once you understand your actual capacity. Many experienced users settle on 20-30 new cards daily as a long-term sustainable pace.

Make Cards That Actually Work

Spaced repetition is only as good as your cards. A few principles:

One idea per card. "Name all the bones in the hand" is a bad card. "What bone is located here?" with an image pointing to the scaphoid is good. Small, specific cards give you clearer feedback about what you actually know.

Test both directions when it matters. For vocabulary, you probably want cards for both recognition (seeing the word, producing the meaning) and production (seeing the meaning, producing the word). These are different skills that need separate practice.

Add context. A card that just says "1066" and expects "Battle of Hastings" creates shallow knowledge. Better: "In what year did William the Conqueror defeat Harold at Hastings?" Context helps you understand, not just parrot.

Use images when they help. For anatomy, geography, or anything visual, pictures are powerful. The visualization and association principles that work for memory techniques also work for flashcards.

Show Up Every Day

The algorithm only works if you actually do your reviews when scheduled. Skip a few days and reviews pile up. The backlog becomes intimidating. Many people quit at this point.

Most successful users build a daily habit. Reviews typically take 15-30 minutes once you've built up a collection. Morning, lunch break, commute: the specific time matters less than consistency.

If you do fall behind, most software lets you reschedule or reset. It's better to declare "backlog bankruptcy" and start fresh than to abandon the system entirely.

Combine with Other Strategies

Spaced repetition handles retention, but it's not the only tool you need.

Memory techniques like the Memory Palace help with initial encoding. Use them to get information into your head effectively, then use spaced repetition to keep it there.

Understanding matters too. You can memorize that mitochondria are "the powerhouse of the cell," but actually understanding cellular respiration requires more than flashcards. Spaced repetition works best for the factual components that support deeper understanding.

What Spaced Repetition Is Best For

The technique shines when you need to memorize a lot of facts and remember them reliably over time: vocabulary, terminology, dates, formulas, anatomy, legal rules, pharmacology, historical facts.

Medical students are among the heaviest users. It's common for med students to maintain Anki decks with 10,000+ cards covering everything from drug mechanisms to diagnostic criteria. Law students use it for rules and case holdings. Language learners use it for vocabulary. Programmers use it for syntax, shortcuts, and API details.

The common thread: high volume and long-term retention. If you need to memorize thousands of items and remember them for years, spaced repetition is probably the most efficient approach that exists.

What It's Less Suited For

Spaced repetition is less helpful for material requiring deep understanding rather than recall. You can memorize that F = ma, but learning to apply it to physics problems requires worked examples and practice, not flashcards.

Skills requiring judgment and integration (writing, diagnosis, design, analysis) don't fit neatly into flashcard format. You might use spaced repetition for the component facts, but the higher-level skill needs different practice.

For information you only need briefly (a one-time presentation, an exam you'll never revisit), the setup overhead may not be worth it. Cramming, despite its inefficiency, does work in the very short term.

Common Questions

How long until I notice results?

You won't see much difference in the first few days. The advantage shows up over weeks and months, when crammed material would be forgotten but spaced material remains accessible. Studies typically show the biggest differences at retention intervals of one week or longer.

Paper cards or software?

For smaller collections (under a few hundred cards), paper works fine and has advantages: no screen time, tactile engagement, simplicity. For large volumes or long-term use, software handles the scheduling logistics much better.

What if I miss a day?

Occasional missed days aren't catastrophic. The algorithm adjusts. Consistent multi-day gaps cause more problems because reviews accumulate. Even 10 minutes of reviews on a busy day is better than nothing.

Is there a limit to how much I can learn this way?

Practically, yes. Your daily review time scales with collection size. At some point, you're spending hours on reviews with little time for new material. Most people find a steady state where they're learning new material while maintaining what they've already learned, typically with 20-45 minutes of daily reviews.

Getting Started

Simple paper start: Make 20 flashcards on something you want to learn. Review them all today. Tomorrow, try to recall each one before looking at the answer. Set aside cards you get right for review in 3 days. Cards you miss, review again tomorrow. Repeat, gradually extending intervals for cards you consistently remember.

Software start: Download Anki (free on desktop and Android; paid on iOS). Browse shared decks for something you're interested in, or create 10 cards of your own. Do your reviews daily for two weeks. See how it feels before scaling up.

The technique rewards consistency over intensity. Twenty minutes daily beats two hours on the weekend. The algorithm handles the scheduling complexity; you just need to show up.

For more on how spacing fits with other learning strategies, see the Learning Strategies page. For the science of how memory works at a deeper level, see How Memory Works.

Note: This page provides general educational information about learning strategies. See my Editorial Standards for how I approach evidence.

References & Research

I've reviewed these sources and selected them for their relevance to understanding spaced repetition. Here's what each contributes:

1. Cepeda, N.J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J.T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). "Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis." Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354-380. Free PDF

Researcher's Note: This meta-analysis examined 839 assessments of distributed practice across 184 articles. It's one of the most comprehensive reviews of spacing research ever conducted. The key practical finding: how long you should wait between reviews depends on how long you need to remember the material. This paper shaped how I think about scheduling reviews.

2. Latimier, A., Peyre, H., & Ramus, F. (2021). "A Meta-Analytic Review of the Benefit of Spacing out Retrieval Practice Episodes on Retention." Educational Psychology Review, 33, 959-987. ResearchGate

Researcher's Note: This recent meta-analysis focused specifically on spaced retrieval practice (the combination of spacing and self-testing that flashcard systems use). The effect size of 0.74 represents a substantial, practically meaningful benefit. This is strong evidence that modern spaced repetition systems work as advertised.

3. Cepeda, N.J., Vul, E., Rohrer, D., Wixted, J.T., & Pashler, H. (2008). "Spacing Effects in Learning: A Temporal Ridgeline of Optimal Retention." Psychological Science, 19(11), 1095-1102. Free PDF

Researcher's Note: This study tested over 1,350 participants to map the relationship between review gaps and retention intervals, up to one year. The practical takeaway: optimal spacing is roughly 10-20% of your target retention interval. If you need to remember something for a year, your first review should be weeks out, not days. This gives the clearest guidance on how to actually schedule reviews.

4. Bjork, R.A., & Bjork, E.L. (1992). "A New Theory of Disuse and an Old Theory of Stimulus Fluctuation." In A. Healy et al. (Eds.), From Learning Processes to Cognitive Processes: Essays in Honor of William K. Estes (Vol. 2, pp. 35-67). Free PDF

Researcher's Note: This paper introduced "desirable difficulties," which explains why techniques that feel harder during learning often produce better retention. Understanding this concept helps you trust the process when spaced practice feels less productive than cramming. The difficulty is a feature, not a bug.

5. Woźniak, P. (1990/2018). "The History of Spaced Repetition." SuperMemo Guru. SuperMemo Wiki

Researcher's Note: Piotr Woźniak developed the algorithms that power most spaced repetition software. This article documents how he created SuperMemo and the SM-2 algorithm (now used in Anki) from personal archives going back to 1985. It's a fascinating primary source on how computational spaced repetition was invented.

6. Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K.A., Marsh, E.J., Nathan, M.J., & Willingham, D.T. (2013). "Improving Students' Learning With Effective Learning Techniques." Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58. ResearchGate

Researcher's Note: This landmark review evaluated ten popular learning techniques against rigorous evidence standards. Distributed practice (spacing) and practice testing were the only two to receive the highest "high utility" rating. Re-reading and highlighting, which students prefer, were rated low. If you read one paper on study techniques, make it this one.

7. Kim, S.K., & Webb, S. (2022). "The Effects of Spaced Practice on Second Language Learning: A Meta-Analysis." Language Learning, 72(1), 269-319. ResearchGate

Researcher's Note: This meta-analysis focused on second language learning, examining 98 effect sizes from 48 experiments. The findings confirm spacing benefits vocabulary acquisition, the most common use of spaced repetition for language learners. Useful if you're using flashcards for language study.

8. Price, D.W., Wang, T., O'Neill, T.R., et al. (2025). "The Effect of Spaced Repetition on Learning and Knowledge Transfer in a Large Cohort of Practicing Physicians." Academic Medicine, 100(1), 94-102. PubMed

Researcher's Note: This study of over 26,000 physicians showed that spaced repetition improved both learning and knowledge transfer in a real-world professional context. Particularly valuable because it demonstrates spacing works for practicing professionals, not just students in lab settings.

9. Bego, C.R., Lyle, K.B., et al. (2024). "Single-paper meta-analyses of the effects of spaced retrieval practice in nine introductory STEM courses." International Journal of STEM Education, 11:9. Free full text

Researcher's Note: This study examined spaced practice across nine STEM courses. The mixed results (strong effects in some courses, weaker in others) are honest and useful for understanding when spacing helps most. Real-world classroom studies like this are rarer than lab studies and valuable for that reason.

Published: 01/04/2026

Last Updated: 01/04/2026

Newest / Popular

Multiplayer

Board Games

Card & Tile

Concentration

Math / Memory

Puzzles A-M

Puzzles N-Z

Time Mgmt

Word Games

- Retro Flash -

Also:

Bubble Pop

• Solitaire

• Tetris

Checkers

• Mahjong Tiles

•Typing

No sign-up or log-in needed. Just go to a game page and start playing! ![]()

Free Printable Puzzles:

Sudoku • Crosswords • Word Search

Hippocampus? Working memory? Spaced repetition?

Look up memory or brain terms in the A-Z glossary of definitions.