Memory Glossary: Key Terms Explained

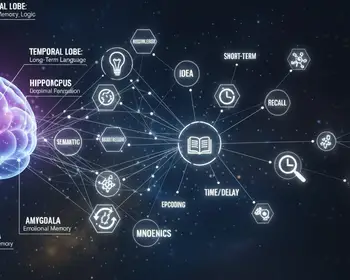

Understanding how memory works starts with knowing the language. This glossary covers the key terms you'll encounter as you explore memory improvement techniques - from brain regions like the hippocampus to practical methods like spaced repetition and the memory palace.

Each definition explains not just what the term means, but why it matters for improving your memory. Use the alphabetical links below to jump to any section.

For practical techniques you can apply right away, visit my Quick Memory Tips page or explore How to Get a Better Memory.

Jump to: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | T | V | W

A

- Acronym

A word formed from the first letters of a series of words you want to remember. "HOMES" for the Great Lakes (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior) is a classic example. Acronyms work as mnemonics because they compress multiple items into a single, memorable word. The best acronyms form real or pronounceable words, making them easier to recall than random letter strings.

- Acrostic

A sentence or phrase where the first letter of each word represents something you want to remember. "Every Good Boy Does Fine" helps music students remember the lines of the treble clef (E, G, B, D, F). Unlike acronyms, acrostics create a full sentence, which can make them more memorable and easier to recall in order. The sillier or more vivid the sentence, the better it tends to stick.

- Active Recall

A learning strategy where you actively stimulate your memory by trying to retrieve information rather than passively reviewing it. Instead of rereading your notes, you close the book and try to remember what you just read. Research consistently shows active recall is far more effective for long-term retention than passive review methods like highlighting or rereading.1 Flash cards and self-testing are common active recall techniques.

- Amygdala

An almond-shaped structure deep in the brain that processes emotions, particularly fear and anxiety. The amygdala works closely with the hippocampus to attach emotional significance to memories, which is why emotionally charged events are often remembered more vividly than neutral ones. This connection explains why you might remember exactly where you were during a shocking news event but forget what you had for lunch last Tuesday.

- Anterograde Amnesia

The inability to form new memories after a brain injury or illness, while memories from before the damage remain largely intact. The famous case of patient H.M., who had his hippocampus removed to treat epilepsy in 1953, demonstrated this dramatically - he could remember his past but couldn't form new long-term memories. This condition helped scientists understand the hippocampus's crucial role in memory formation. Compare with retrograde amnesia.

- Association

The mental connection between two or more pieces of information. Association is fundamental to how memory works - your brain stores new information by linking it to things you already know. Memory techniques like mnemonics and the memory palace deliberately create strong, vivid associations to make information more memorable.

- Attention

The cognitive process of selectively focusing on specific information while filtering out distractions. Memory expert Harry Lorayne calls this "Original Awareness" - without paying attention to information in the first place, a memory simply cannot form. This is why multitasking while trying to learn usually fails; divided attention leads to weak or nonexistent memories. See also Concentration.

- Autobiographical Memory

Memory for the events and facts of your own life - your personal history. Autobiographical memory combines episodic memory (specific events like your graduation day) with semantic memory (facts about yourself like where you grew up). These memories form the narrative of who you are and tend to be organized around major life periods and emotionally significant events.

B

- BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor)

A protein that supports the survival and growth of neurons and promotes the formation of new neural connections. Often called "fertilizer for the brain," BDNF plays a crucial role in learning, memory, and neuroplasticity. Aerobic exercise is one of the most effective ways to boost BDNF levels, which helps explain why physical activity improves cognitive function and memory.

- Brain Training

Activities designed to maintain or improve cognitive abilities like memory, attention, and processing speed. Brain training can include puzzles, memory games, learning new skills, or computerized cognitive exercises. While the extent to which brain training "transfers" to real-world improvements is debated, engaging in mentally challenging activities does support overall brain health and may help build cognitive reserve.

C

- Cerebral Cortex

The outermost layer of the brain, responsible for higher cognitive functions including thinking, reasoning, language, and voluntary movement. The cortex is where long-term memories are ultimately stored after being processed by the hippocampus. Different regions specialize in different functions - the prefrontal cortex handles executive functions, while the temporal lobe is crucial for memory and language.

- Chunking

A strategy for organizing information into smaller, manageable units or "chunks" to make it easier to remember. Your working memory can only hold about 4-7 items at once,2,3 but chunking lets you pack more information into each slot. Phone numbers use chunking naturally (555-867-5309 is easier than 5558675309), and you can apply the same principle to any information you need to memorize.

- Cognitive Load

The total amount of mental effort being used in working memory at any given time. When cognitive load is too high - too much information coming in at once - learning suffers because working memory becomes overwhelmed. Effective learning involves managing cognitive load by breaking complex material into digestible pieces and eliminating unnecessary distractions.

- Cognitive Reserve

The brain's resilience against damage or age-related decline, built up through education, mentally stimulating activities, and rich life experiences. People with higher cognitive reserve can often maintain normal function longer even as their brains show physical signs of aging or disease. This concept explains why staying mentally active throughout life may help protect against dementia.

- Concentration

The ability to direct and sustain attention on a specific task or piece of information. Concentration is the gateway to memory - without it, information never gets properly encoded in the first place. Techniques to improve concentration include eliminating distractions, taking regular breaks, deep breathing, physical exercise, and practicing focused attention through activities like meditation. See my concentration tips for more strategies.

- Consolidation

The process by which short-term memories are transformed into stable, long-term memories. Consolidation happens primarily during sleep, which is why pulling an all-nighter before an exam often backfires - you're preventing your brain from solidifying what you've learned. The hippocampus plays a central role, gradually transferring memories to other brain regions for permanent storage. See also Sleep Consolidation.

- Context-Dependent Memory

The phenomenon where information is easier to recall when you're in the same environment where you originally learned it. If you studied in a quiet library, you may remember the material better when tested in a similar setting. This happens because environmental cues become linked to memories and can serve as retrieval triggers.

- Cramming

Intensive studying done shortly before an exam or deadline, attempting to absorb large amounts of information in a single session. While cramming can produce short-term recall for a test the next day, it's highly ineffective for long-term retention. Research consistently shows that spaced repetition - spreading study sessions over time - leads to far more durable memories than massed practice.4

- Cue (Memory Cue)

Any stimulus that helps trigger the retrieval of a memory. Cues can be external (a song, a smell, a location) or internal (a related thought or emotion). The memory palace technique works by creating deliberate spatial cues that help you retrieve information in a specific order. The more distinctive and personally meaningful the cue, the more effective it tends to be.

D

- Declarative Memory

Memory for facts and events that can be consciously recalled and "declared" or stated. This includes both semantic memory (general knowledge like "Paris is the capital of France") and episodic memory (personal experiences like "I visited Paris in 2019"). Declarative memory depends heavily on the hippocampus and is distinct from procedural memory.

- Desirable Difficulty

A learning condition that makes initial learning harder but improves long-term retention and transfer. Examples include spacing out practice, interleaving different topics, and testing yourself rather than rereading. These strategies feel harder and slower in the moment, which is why students often avoid them - but the extra effort during learning pays off in stronger, more durable memories.

- Distributed Practice

Another term for spaced repetition - spreading learning sessions out over time rather than cramming. Research dating back to Ebbinghaus in the 1880s has consistently shown that distributed practice leads to much better long-term retention than massed practice (studying everything in one sitting), even when total study time is the same.4,5

- Dual Coding

A learning strategy that combines verbal and visual information to create stronger memories. When you read about a concept and also see a diagram, or when you create a mental image to represent an abstract idea, you're using dual coding. The theory, developed by Allan Paivio in 1971,6 suggests that information encoded in two different formats (verbal and visual) creates more retrieval pathways than information encoded in just one format.

E

- Elaborative Rehearsal

A memory strategy that involves thinking deeply about information and connecting it to things you already know, rather than simply repeating it. Asking yourself "How does this relate to what I learned last week?" or "Why does this matter?" creates richer memory traces than mindless repetition. This is why teaching something to someone else is such an effective way to remember it.

- Encoding

The first stage of memory formation, where your brain converts information from your senses into a form that can be stored. Think of it like saving a file to your computer - if the file doesn't save properly, you won't be able to open it later. Encoding is influenced by attention, emotional state, and how deeply you process the information. Weak encoding is a common reason for forgetting.

- Episodic Memory

Memory for personal experiences and specific events in your life, including when and where they happened. Remembering your wedding day, your first day at a new job, or what you did last weekend are all examples of episodic memory. These memories have a strong sense of "mental time travel" - when you recall them, you often feel like you're reliving the experience. The hippocampus is essential for forming new episodic memories.

F

- False Memory

A memory of an event that didn't happen, or a significantly distorted memory of a real event. Research by Elizabeth Loftus and others has shown that memories can be surprisingly malleable - leading questions, suggestions, and imagination can create convincing false memories.7 This doesn't mean memory is unreliable for everyday purposes, but it does explain why eyewitness testimony can be flawed and why flashbulb memories aren't always accurate despite feeling vivid.

- Flashbulb Memory

A vivid, detailed memory of a surprising or emotionally significant event, like where you were when you heard shocking news. These memories feel like mental photographs and are often recalled with high confidence. However, research shows flashbulb memories aren't necessarily more accurate than ordinary memories - they just feel more real because of their emotional intensity. See also False Memory.

- Forgetting Curve

A model developed by Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885 showing how quickly we forget new information over time.5 The curve demonstrates that forgetting is fastest immediately after learning - without review, people may forget 50% of new information within an hour and up to 90% within a month. The good news: spaced repetition can flatten the curve dramatically, making memories far more durable.

G

- Generation Effect

The finding that information you generate yourself is remembered better than information you simply read or hear. Writing a summary in your own words, solving a problem yourself (rather than reading the solution), or creating your own mnemonics all take advantage of this effect. The extra mental effort involved in generating information creates stronger memory traces than passive reception.

H

- Hippocampus

A seahorse-shaped brain structure in the temporal lobe that's essential for forming new declarative memories and spatial navigation. Rather than storing memories permanently, the hippocampus acts as a processing center that helps transfer information from short-term to long-term storage, primarily during sleep. Damage to the hippocampus (as seen in early Alzheimer's disease) impairs the ability to form new memories while leaving older memories relatively intact.

I

- Imagery (Mental Imagery)

The process of creating mental pictures to represent information. The brain remembers images more easily than abstract words or concepts (a phenomenon called the "picture superiority effect"), which is why visualization is central to powerful memory techniques like the memory palace. The more vivid, unusual, and emotionally engaging the mental image, the more memorable it becomes.

- Implicit Memory

Memory that influences your behavior without conscious awareness. This includes procedural memory (skills like riding a bike), priming effects (where exposure to one thing influences your response to something else), and conditioned responses. Unlike declarative memory, implicit memory doesn't require the hippocampus and can remain intact even when conscious memory is severely impaired.

- Interference

When other memories or information disrupt your ability to remember something. Proactive interference occurs when old memories make it harder to learn new things (like when your old phone number keeps popping into your head). Retroactive interference is the opposite - new learning disrupts older memories. Interference is one of the main causes of forgetting and explains why similar information is often confused.

- Interleaving

A learning strategy where you mix different topics or types of problems during practice, rather than focusing on one thing at a time. While interleaving can feel harder and slower than blocked practice, research shows it leads to better long-term retention and the ability to apply knowledge in new situations.8 It forces your brain to continually retrieve and distinguish between different concepts. Interleaving is an example of desirable difficulty.

L

- Long-Term Memory

The brain's system for storing information over extended periods, from hours to a lifetime. Unlike working memory, long-term memory has essentially unlimited capacity. Information must be encoded and consolidated to enter long-term storage, and retrieval depends on having effective cues. Long-term memory includes declarative memory (facts and events) and implicit memory (skills and unconscious learning).

- Long-Term Potentiation (LTP)

A process where repeated stimulation of neurons strengthens the synaptic connections between them, making future communication along that pathway easier. LTP is thought to be one of the main cellular mechanisms underlying learning and memory formation. The phrase "neurons that fire together wire together" (Hebb's rule) describes this principle - the more you use a neural pathway, the stronger it becomes.

- Loci (Method of Loci)

See Memory Palace.

M

- Memory Consolidation

See Consolidation.

- Memory Palace (Method of Loci)

An ancient memory technique where you visualize a familiar location (like your home) and mentally place items you want to remember at specific spots along a path through that space. To recall the information, you simply "walk" through the palace in your mind, encountering each item. The technique was invented by the Greek poet Simonides around 500 BC and is still used by memory champions today to memorize thousands of digits, cards, or words. It works because the brain has powerful spatial memory systems, and linking abstract information to vivid locations makes it far more retrievable.

- Memory Trace (Engram)

The physical change in the brain that represents a stored memory. Scientists have debated for over a century exactly what form memory traces take, but current research suggests they involve changes in the strength of synaptic connections between networks of neurons. Memory traces can be strengthened through repetition and consolidation, or weakened through disuse and interference.

- Metacognition

Thinking about your own thinking - awareness of how well you understand and remember something. Good metacognition helps you study more effectively because you can accurately judge what you know and what needs more work. Poor metacognition leads to overconfidence (thinking you know something when you don't) and inefficient studying. Testing yourself is one of the best ways to improve metacognitive accuracy.

- Mnemonics

Memory aids that use patterns, associations, or structures to make information easier to remember. Examples include acronyms (like "HOMES" for the Great Lakes), acrostics ("Every Good Boy Does Fine"), rhymes ("In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue"), and the memory palace. Mnemonics work by giving abstract information a more concrete, memorable form and by connecting new information to things you already know.

N

- Neuron

A nerve cell - the basic building block of the brain and nervous system. Neurons communicate with each other through electrical and chemical signals, transmitting information across synapses. The human brain contains roughly 86 billion neurons, and learning involves changing the connections between them. When you form a new memory, neurons that fire together strengthen their connections (long-term potentiation).

- Neurogenesis

The process of generating new neurons in the brain. Once thought impossible in adults, research has shown that neurogenesis does occur in certain brain regions, particularly the hippocampus. Physical exercise, learning new things, and reducing chronic stress appear to promote neurogenesis, while aging and depression may reduce it. The role of these new neurons in memory is still being studied.

- Neuroplasticity

The brain's ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. Whenever you learn something, your brain physically changes - synapses strengthen, new connections form, and neural pathways are modified. This adaptability means your brain is never "fixed" and can continue to develop new capabilities at any age. Neuroplasticity is what makes memory improvement possible and underlies recovery from brain injuries.

O

- Overlearning

Continuing to practice or study material even after you can recall it perfectly. Ebbinghaus found that overlearning slows the rate of forgetting.5 While there are diminishing returns (you don't need to practice forever), a few extra repetitions after you think you've "got it" can significantly improve long-term retention. This is especially useful for information you need to recall under pressure, like during a test or presentation.

P

- Peg System

A mnemonic technique where you memorize a fixed list of "pegs" (like rhymes or images for numbers 1-10), then hang new information on these pegs through vivid associations. For example, if "one" is paired with "sun," you'd visualize the first item on your list interacting with the sun. Unlike the memory palace, the peg system doesn't require a physical location but provides a similar structure for organizing and retrieving information.

- Prefrontal Cortex

The front part of the brain, behind the forehead, responsible for executive functions including attention, planning, decision-making, and working memory. The prefrontal cortex helps you hold information in mind, resist distractions, and strategically organize your thinking. It's one of the last brain regions to fully develop (not until the mid-20s) and is vulnerable to the effects of stress, sleep deprivation, and aging.

- Primacy Effect

The tendency to remember items at the beginning of a list better than those in the middle. This happens because the first items get more rehearsal time and are more likely to be transferred to long-term memory. Together with the recency effect, it creates the "serial position curve" - a U-shaped pattern where items at the beginning and end of lists are remembered best.

- Priming

A form of implicit memory where exposure to one stimulus influences your response to a later stimulus, without conscious awareness. If you recently saw the word "yellow," you'd be faster to recognize "banana" because the concepts are linked in memory. Priming demonstrates that memory influences us in ways we don't consciously notice.

- Procedural Memory

Memory for skills and how to do things - riding a bike, typing, playing an instrument. Unlike declarative memory, procedural memories are expressed through performance rather than conscious recall, and they don't depend on the hippocampus. This is why people with amnesia can still learn new motor skills even though they can't remember the practice sessions.

- Prospective Memory

Remembering to do something in the future - take medication at noon, call someone back, stop at the store on the way home. Unlike retrospective memory (remembering past events), prospective memory requires you to remember an intention at the right time or in the right context. It's particularly vulnerable to distraction, which is why external cues like alarms, notes, and placing objects in visible spots are so helpful for prospective memory tasks.

R

- Recall

Retrieving information from memory without any cues or prompts, like answering an essay question or trying to remember someone's name. Recall is more difficult than recognition and provides a stronger test of memory. Practicing recall (through self-testing or active recall) is one of the most effective ways to strengthen memories.

- Recency Effect

The tendency to remember the most recent items in a list better than those in the middle. This occurs because the last few items are still in working memory when you try to recall them. Unlike the primacy effect, recency effects are temporary and disappear if recall is delayed even briefly.

- Recognition

Identifying previously encountered information when you see it again, like recognizing a face or picking the right answer on a multiple-choice test. Recognition is generally easier than recall because the information itself serves as a cue. This is why you might recognize someone's face but be unable to recall their name.

- Rehearsal

The mental process of repeating information to keep it in memory. Simple or "maintenance" rehearsal (just repeating something over and over) can keep information in working memory temporarily but is not very effective for long-term retention. Elaborative rehearsal, which involves thinking deeply about meaning and connections, is far more effective for creating lasting memories.

- Retrieval

The process of accessing stored memories when you need them. Retrieval is the third stage of memory (after encoding and storage) and depends heavily on having good cues. Many cases of "forgetting" are actually retrieval failures - the memory is stored but you can't access it. This is why a hint or reminder can suddenly bring a "lost" memory flooding back.

- Retrieval Practice

See Active Recall.

- Retrograde Amnesia

The loss of memories formed before a brain injury or illness - the opposite of anterograde amnesia. Someone with retrograde amnesia might not remember their past but can still form new memories. The extent of memory loss varies; often recent memories are more affected than older ones, suggesting that newer memories are more vulnerable because they haven't been fully consolidated.

S

- Semantic Memory

Memory for general knowledge and facts about the world, independent of personal experience. Knowing that dogs are mammals, that Paris is in France, or that 2+2=4 are examples of semantic memory. Unlike episodic memory, semantic memories don't include information about when or where you learned something - the facts feel like things you've "always known."

- Sensory Memory

The brief, automatic retention of sensory information immediately after perception. Iconic memory (visual) lasts about a quarter second; echoic memory (auditory) lasts 3-4 seconds. Sensory memory holds far more information than you can consciously process, but it fades almost instantly unless you pay attention to it. Think of it as the first filter that determines what even has a chance of being remembered.

- Short-Term Memory

The capacity to hold a small amount of information in mind for a brief period (typically 15-30 seconds) without rehearsal. Often used interchangeably with working memory, though working memory emphasizes the active manipulation of information rather than just passive storage. Short-term memory has limited capacity - about 4-7 items2,3 - which is why chunking is such a valuable strategy.

- Sleep Consolidation

The process by which sleep strengthens and stabilizes memories formed during waking hours. During sleep (especially deep slow-wave sleep and REM sleep), the brain replays the day's experiences, transferring information from the hippocampus to the cortex for long-term storage. This is why a good night's sleep after studying is so important - and why cramming all night usually backfires.

- Source Memory

Memory for where, when, or how you learned a piece of information - not just the information itself. You might remember a fact but forget whether you read it in a book, heard it from a friend, or saw it online. Source memory is handled by different brain processes than memory for content, which is why the two can become separated. Poor source memory can contribute to false memories and confusion about what's real.

- Spaced Repetition

A learning technique where you review information at gradually increasing intervals rather than cramming. First review might come an hour after learning, then a day later, then a few days, then a week, and so on. Each successful recall strengthens the memory and allows you to wait longer before the next review. Spaced repetition is one of the most powerful and well-researched techniques for long-term retention,4 directly countering the forgetting curve.

- State-Dependent Memory

The phenomenon where information is easier to recall when you're in the same physical or emotional state as when you learned it. If you learned something while caffeinated, you may remember it better while caffeinated again. Like context-dependent memory, this occurs because your internal state becomes linked to the memory and can serve as a retrieval cue.

- Synapse

The junction between two neurons where information passes from one cell to another. When you learn something new, synapses are strengthened or weakened, and new synaptic connections can form - this is the physical basis of memory. The process of strengthening synapses through repeated use is called long-term potentiation and is summarized by the phrase "neurons that fire together wire together."

T

- Temporal Lobe

The region of the brain located on the sides of the head, near the temples. The temporal lobes are crucial for memory, language, and auditory processing. The hippocampus and amygdala are located within the temporal lobes. Damage to this area can severely impair the ability to form new memories or to understand and produce language.

- Testing Effect

The finding that being tested on material (or testing yourself) improves long-term retention more than spending the same time restudying.1 Even if you get answers wrong, the act of trying to retrieve information strengthens memory more than passive review. This is why practice tests, flash cards, and self-quizzing are so effective - the struggle to remember is itself a powerful learning experience. Also called the retrieval practice effect.

- Tip-of-the-Tongue State

The frustrating feeling of knowing that you know something but being temporarily unable to retrieve it. You might remember the first letter, how many syllables it has, or related information, but the target word won't come. This phenomenon demonstrates that retrieval is an active process that can fail even when the memory is clearly stored. The word usually pops into mind later when you stop trying so hard.

- Transfer

The ability to apply knowledge or skills learned in one context to new situations. Near transfer involves applying learning to very similar situations; far transfer involves applying it to quite different ones. Effective learning strategies like interleaving and active recall tend to promote better transfer than passive review or blocked practice. Transfer is often the ultimate goal of education - not just remembering, but being able to use what you've learned.

V

- Visualization

The deliberate creation of mental images to aid memory and learning. Visualization is a core technique in many mnemonic systems, including the memory palace and peg system. The brain's visual processing systems are powerful and well-developed, so converting abstract information into vivid mental pictures takes advantage of this capacity. Effective visualization involves making images vivid, unusual, emotionally engaging, and personally meaningful.

W

- Working Memory

The cognitive system that temporarily holds and manipulates information you're actively thinking about. Working memory is essential for reasoning, learning, and comprehension - it's where you do your mental work. The capacity is limited (roughly 4 items for most people3), which is why complex problems are hard to solve entirely in your head and why chunking and external aids (like writing things down) are so helpful.

Related Resources

Now that you know the terminology, put it into practice:

Quick Memory Tips - Practical techniques you can use right now

How to Get a Better Memory - A comprehensive guide to memory improvement

How Memory Works - Understanding the science behind your memory

Memory Systems - Advanced mnemonic techniques explained

Free Memory Games - Practice and strengthen your memory

[+] Scientific References

Published: 12/19/2025

Last Updated: 12/19/2025

Newest / Popular

Multiplayer

Board Games

Card & Tile

Concentration

Math / Memory

Puzzles A-M

Puzzles N-Z

Time Mgmt

Word Games

- Retro Flash -

Also:

Bubble Pop

• Solitaire

• Tetris

Checkers

• Mahjong Tiles

•Typing

No sign-up or log-in needed. Just go to a game page and start playing! ![]()

Free Printable Puzzles:

Sudoku • Crosswords • Word Search

Hippocampus? Working memory? Spaced repetition?

Look up memory or brain terms in the A-Z glossary of definitions.