- Home

- Memory Skills

- Learning Strategies

Learning Strategies: How to Make Information Stick

You can encode information perfectly using the Memory Palace or other memory techniques, but if you don't review it strategically, it will fade. That's the retention problem: keeping information accessible over time.

Most people approach retention wrong. They re-read material multiple times, highlight everything, and cram the night before exams. Research shows conclusively that these popular methods produce weak, fragile memories that evaporate quickly.[1]

The strategies that actually work feel harder while you're using them, which is exactly why most students avoid them. Spacing out your study sessions feels less productive than cramming. Testing yourself feels uncomfortable compared to passively reviewing notes. But discomfort during learning predicts durability afterward.

This page covers five core learning strategies that strengthen retention: reducing interference, spacing practice over time, balancing whole and part learning, active recall through self-testing, and using structured study systems. These aren't trendy techniques. They're principles that decades of research confirm work across subjects, age groups, and learning contexts.[2]

Why Retention Fails: The Forgetting Curve

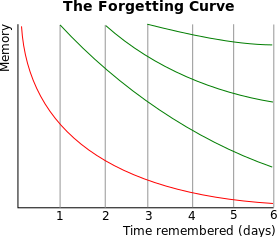

Hermann Ebbinghaus discovered something depressing in 1885: we forget most of what we learn, and we forget it fast. His experiments on himself showed that without review, roughly 50-80% of newly learned information vanishes within days.[3]

The forgetting curve describes this predictable decline. You learn something today, and your memory is strong. Tomorrow, it's noticeably weaker. A week later, you might remember fragments. A month out, it's mostly gone unless something intervened.

Two things make this worse. First, we don't realize how much we've forgotten until we try to recall it. Re-reading your notes feels like remembering, but recognition (seeing information again) is much easier than recall (retrieving it without prompts). Second, forgetting accelerates when new information interferes with old, which happens constantly in school or work.

The good news: every time you successfully retrieve a memory, you strengthen it and slow its decay. The forgetting curve can be beaten, but only through strategic practice. In the image above, the green lines are flattened curves after repetitions showing that fewer and less frequent repetitions are needed to retain knowledge.

Strategy 1: Reduce Interference

Interference happens when similar information competes in your memory. You study Spanish vocabulary, then French vocabulary, and the two languages blur together. You learn one programming language's syntax, then another's, and mix up which brackets go where.

This is called proactive and retroactive interference. Old memories interfere with new (proactive), or new memories interfere with old (retroactive). The result is confusion when you try to recall details.

Here's how to minimize it:

Overlearn the Material

Overlearning means continuing to study well beyond the point where you can barely recall the information. If you're memorizing a speech, don't stop after one error-free recitation. Run through it five more times. The additional practice creates stronger memory traces that resist interference.

Research shows that overlearning particularly helps with retention under pressure. Material you've overlearned stays accessible even when you're stressed or distracted, precisely the conditions where interference typically strikes.[4]

Overlearning feels inefficient because you're practicing something you "already know." That feeling is misleading. You're building the durability that lets you actually use the information later.

Make Material Meaningful

Rote memorization creates weak memories vulnerable to interference. When information connects to what you already understand or to vivid mental images, it becomes distinctive and resistant to confusion.

If you're studying chemistry and trying to remember that water is H₂O, you could memorize it by repetition. Or you could visualize two hydrogen atoms (imagine tiny H letters) bonding with one oxygen atom (a big O), perhaps picturing them as cartoon characters holding hands. The visualization creates a unique memory that's harder to confuse with other molecular formulas.

Use these approaches to add meaning:

Build on what you know. Connect new information to existing knowledge. If you already understand photosynthesis, learning about cellular respiration becomes easier because you see how they're inverse processes. Familiarity with one domain accelerates learning in related areas.

Create visual mnemonics. Convert abstract information into vivid mental images, especially bizarre or humorous ones. The distinctiveness protects against interference. The capital of Chile? Picture Santa eating a giant bowl of chili. Santiago becomes unforgettable.

Look for patterns. When memorizing phone numbers, historical dates, or code snippets, identify repeating patterns. Pattern recognition transforms random details into meaningful structures.

Separate Similar Subjects

If you need to study biochemistry and organic chemistry in the same week, don't study them back-to-back. Insert a different subject between them. Study biochemistry, then statistics, then organic chemistry. The unrelated material in between reduces interference.

When studying similar subjects is unavoidable, create distinct contexts for each. Studies demonstrate that studying French in one room and Spanish in another room reduces cross-language confusion. Even using different colored pens for notes or different background music can help your brain keep them separate.[5]

The same principle applies to memory techniques. If you're using the Memory Palace for both French and Spanish vocabulary, use completely different locations for each language to prevent mental cross-contamination.

Strategy 2: Space Your Practice

Spacing, also called distributed practice or spaced repetition, means spreading your study sessions over time rather than massing them together. Study a chapter for one hour today, one hour tomorrow, and one hour the day after, rather than three hours in a single marathon session.

This is perhaps the most thoroughly researched principle in learning science. Hundreds of studies across more than a century show that spaced practice produces dramatically better long-term retention than cramming, often by 200% or more.[6]

Why does spacing work so well?

Your Brain Consolidates During Breaks

Memory consolidation, the process of converting temporary memories into stable ones, happens largely during rest and sleep. When you space out learning, you give your brain multiple consolidation windows. Each break between sessions allows the memory to strengthen.

Cramming denies your brain those breaks. You're trying to force everything through the consolidation process at once, which creates a bottleneck.

Retrieval Gets Harder, Which Makes Memory Stronger

When you review material after a delay, recall requires more effort than reviewing immediately. That difficulty is desirable. Research shows that the harder your brain has to work to retrieve a memory (up to a point), the more that retrieval strengthens the memory.[7]

This is called "desirable difficulty." If you review material before you've had a chance to forget it, retrieval is too easy to provide much benefit. Wait until recall requires real effort, and each successful retrieval makes the memory substantially more durable.

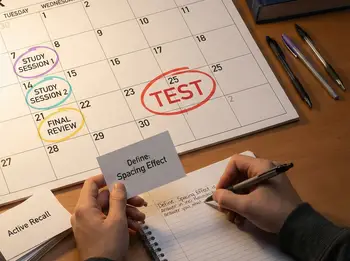

How to Space Effectively

The optimal spacing intervals depend on how long you need to remember something. For an exam in one week, review material daily. For long-term retention measured in months or years, follow an expanding schedule: review after one day, then three days, then one week, then two weeks, then one month.

Software like Anki automates this calculation, showing you flashcards just before you're likely to forget them. But you don't need software. A simple calendar and self-discipline work fine.

The key insight: total study time often decreases with spacing. You might need three hours of cramming to barely pass an exam, but two hours distributed across several days to achieve solid retention. Spacing isn't just more effective; it's often more efficient.

For a deeper look at spacing intervals, software options like Anki, and practical implementation tips, see the dedicated Spaced Repetition page.

Strategy 3: Balance Whole and Part Learning

When facing a large chapter or complex material, should you read straight through (whole learning) or break it into sections and study them separately (part learning)? Research suggests the answer is often both, in strategic combination.

The Whole-Part-Whole Method

Start by reading through all the material quickly once or twice to grasp the overall structure. Don't try to memorize details yet. Just build a mental framework.

Then break the material into logical sections and study each part carefully, using the retention strategies on this page. Work through each section until you understand it well.

Finally, review everything from beginning to end again. This final whole review helps you see how the parts connect and reinforces the overall structure.

This method works particularly well for long or difficult material because the initial whole-learning pass creates context that makes the parts easier to learn, while the final whole review prevents you from losing sight of how everything fits together.

The Progressive Part Method

Another approach: study the first section, then study the second section while also reviewing the first, then study the third section while reviewing the first and second, and so on.

This progressive review prevents you from forgetting early material while you work through later sections. It also helps you notice connections between parts that you might miss if you studied each section in isolation.

The Serial Position Effect

Here's a quirk of memory worth knowing: items at the beginning and end of a list are easiest to remember, while items in the middle are hardest. This is the "serial position effect."

If you're memorizing a list and can rearrange it, put the more difficult items at the beginning and end where they'll benefit from the natural advantage. Put easier items in the middle where memory is weakest.

If you can't rearrange the material, spend extra time on the middle sections to compensate for the disadvantage.

Strategy 4: Test Yourself (Active Recall)

This is the strategy students resist most despite it being one of the most powerful. Instead of re-reading your notes or textbook, close the material and try to recall the information from memory. Write it down, say it aloud, or explain it to someone else, all without looking.

This is called active recall, retrieval practice, or the testing effect. Landmark studies show that testing yourself produces dramatically better long-term retention than reviewing material passively, often improving recall by 50% or more.[8]

Why does testing work so well?

Retrieval Is a Learning Event

Every time you successfully pull a memory out of storage, you strengthen the retrieval pathway to that memory. Passive review doesn't exercise the retrieval machinery, so it doesn't strengthen it.

Think of memory like a trail through a forest. Reading your notes is like looking at a map of the trail. Actually retrieving the information from memory is like walking the trail. Each trip down the path makes it clearer and easier to follow next time.

Testing Reveals Gaps

When you re-read notes, everything looks familiar, which creates an illusion of competence. You think you know the material because you recognize it. Testing yourself reveals what you actually can and can't recall without prompts.

This feedback is invaluable. It tells you exactly where to focus additional study, rather than wasting time reviewing material you already know while neglecting the parts you haven't mastered.

How to Implement Active Recall

After reading a section of your textbook, close the book and try to write down the main points from memory. Compare what you wrote to the actual text. What did you miss? Study those parts again, then test yourself again.

Create flashcards for facts, formulas, or vocabulary. Traditional paper flashcards work, but spaced repetition software like Anki is more efficient because it automatically schedules reviews.

After a lecture or reading session, explain the material aloud to yourself or to someone else. Can you describe the key concepts without referring to notes? If not, you haven't learned it yet.

Work through practice problems without looking at solutions. Struggle with them. The struggle is where learning happens. Only after attempting the problem should you check the answer and review what you missed.

Research by Dunlosky and colleagues rated practice testing as one of the two highest-utility learning techniques, alongside distributed practice. These two strategies, when combined, are extraordinarily effective.[1]

For a deeper exploration of why retrieval practice works, practical methods like the blank page technique and Cornell notes, and guidance on when active recall helps most, see the dedicated Active Recall page.

Strategy 5: Use a Study System

Study systems are structured methods for working through material. They provide a framework so you don't have to figure out what to do next while you're trying to learn.

The most well-known is SQ3R: Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review. Here's how it works:

Survey

Before reading a chapter in detail, skim through it to understand the structure. Read the headings, subheadings, chapter summary, and any highlighted terms or graphs. This preview creates a mental framework for organizing the details you'll learn.

Surveying takes five to ten minutes but substantially improves comprehension and retention of the material that follows.

Question

Turn headings into questions. If a section is titled "Photosynthesis," ask yourself "What is photosynthesis?" and "How does photosynthesis work?" These questions give you a purpose for reading beyond passive absorption.

Good questions focus your attention and create expectation. Your brain actively looks for answers as you read, which improves encoding.

Read

Now read the material carefully, looking for answers to your questions. Don't highlight yet. On a first pass, it's difficult to judge what's actually important.

On subsequent passes, take notes, create summaries, work through examples, and mark key points sparingly. Active engagement with the material, not passive highlighting, drives retention.

Recite

After each section, close the book and recite the main points from memory. This is active recall in action. Can you answer the questions you posed? Can you explain the key concepts without looking?

Spend at least half your study time reciting rather than reading. This feels uncomfortable because it's harder than reading, but difficulty predicts learning.

Review

After working through the entire chapter, review all the material one more time. Go through your notes, test yourself on the main concepts, and identify anything that still feels shaky.

Then schedule additional reviews using spaced repetition. Review the material tomorrow, again in three days, again in a week. Each review session makes the memory more durable.

Combining the Strategies

These five strategies work best when combined. Here's what an effective study session might look like:

You're studying for a biology exam on cellular respiration. You create a study schedule that spaces your sessions over five days (spacing). You survey the chapter to grasp the overall process, then break it into parts: glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and the electron transport chain (whole-part learning).

For each part, you read carefully, then close the book and try to explain the process from memory (active recall). You create visual mnemonics for the steps to make them distinctive and reduce interference with other metabolic pathways you've learned (reduce interference).

You use SQ3R to structure your approach: survey, question, read, recite, review. After each study session, you update your flashcards and schedule the next review session (study system).

This integrated approach feels harder than reading the chapter three times would feel. But it produces memory that lasts, not just recognition that evaporates after the exam.

A Practical Resource: The Best Study Skills PDF

I've created a detailed guide that expands on these five strategies with specific examples and techniques. The Best Study Skills PDF walks through each principle with concrete applications for students at any level.

The guide draws heavily from Dr. Kenneth Higbee's excellent book Your Memory: How It Works and How to Improve It, which remains one of the most practical treatments of learning strategies based on cognitive science. If you want to go deeper, I recommend finding a copy.

The PDF is free to download, share, and use for any non-commercial purpose.

What the Research Actually Says

If you're skeptical that these strategies work as advertised, I don't blame you. Study tips on the internet are often based on intuition rather than evidence.

But these strategies aren't speculation. The Dunlosky review I referenced earlier evaluated ten common learning techniques using strict evidence standards. Practice testing and distributed practice (spacing) received the highest ratings for effectiveness across diverse materials and learner populations. Highlighting, re-reading, and summarizing, which students rely on heavily, received low ratings.[1]

A more recent study on undergraduate physics students showed 50-125% improvement in problem-solving from using interleaving (mixing different problem types) rather than blocked practice (solving all problems of one type together). Notably, students rated the interleaved practice as more difficult and incorrectly believed they learned less from it.[9]

The pattern repeats across studies: the techniques that feel most effective while learning often produce the weakest retention, while techniques that feel difficult during learning produce the strongest memory.

Trust the research, not your intuitions about what's working.

Where to Go From Here

Start simple. Pick one strategy from this page and actually use it in your next study session. Don't try to implement everything at once.

If you're studying for an exam or learning something for work, spacing and active recall will probably give you the biggest immediate benefit. If you're trying to master a complex subject with lots of similar details, focus on reducing interference through meaningful encoding and context separation.

For a deeper dive into specific techniques, see the pages on Memory Techniques for encoding strategies, and How Memory Works for the underlying cognitive science.

The key is to actually practice these strategies, not just read about them. Retention doesn't improve from understanding the principles. It improves from applying them consistently until they become automatic.

References & Research

I've reviewed these sources and selected them for their relevance to understanding effective learning strategies. Here's what each contributes:

1. Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K.A., Marsh, E.J., Nathan, M.J., & Willingham, D.T. (2013). "Improving Students' Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology." Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58. ResearchGate

Researcher's Note: This landmark review evaluated ten popular learning techniques using strict evidence criteria. Practice testing and distributed practice received the highest utility ratings for improving learning across diverse conditions. Re-reading and highlighting, which students heavily favor, were rated low. This paper should fundamentally change how anyone approaches studying.

2. Roediger, H.L., & Karpicke, J.D. (2006). "Test-Enhanced Learning: Taking Memory Tests Improves Long-Term Retention." Psychological Science, 17(3), 249-255. Free PDF from authors

Researcher's Note: This study demonstrated that taking tests on material produces substantially better long-term retention than additional study time. Students in the testing condition outperformed the studying condition by large margins on delayed tests. The testing effect is one of the most robust findings in learning research.

3. Ebbinghaus, H. (1885/1913). Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology. Free full text

Researcher's Note: The foundational text of experimental memory research. Ebbinghaus's forgetting curve, discovered through painstaking self-experimentation, has been replicated countless times. His central finding remains true 140 years later: without review, we forget most of what we learn, and we forget it rapidly.

4. Rohrer, D., Taylor, K., Pashler, H., Wixted, J.T., & Cepeda, N.J. (2005). "The Effect of Overlearning on Long-Term Retention." Applied Cognitive Psychology, 19(3), 361-374. ResearchGate

Researcher's Note: This study investigated whether continued practice after reaching mastery improves retention. The results showed that overlearning does enhance long-term memory, particularly when intervals between study and test are long. The benefits are modest but real, especially for material that must be retained under pressure.

5. Smith, S.M., & Vela, E. (2001). "Environmental context-dependent memory: A review and meta-analysis." Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 8(2), 203-220. Journal link

Researcher's Note: This meta-analysis examined whether changing contexts between learning and testing affects memory. The findings confirm that environmental context matters: memory is better when tested in the same environment where learning occurred. This explains why studying different subjects in different locations can reduce interference.

6. Cepeda, N.J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J.T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). "Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis." Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354-380. Free PDF

Researcher's Note: This comprehensive meta-analysis synthesizes decades of research on spacing effects. The conclusion is unambiguous: distributing practice over time produces substantially better retention than massing practice into single sessions. The effect is large, consistent, and works across ages and materials.

7. Bjork, R.A., & Bjork, E.L. (1992). "A New Theory of Disuse and an Old Theory of Stimulus Fluctuation." In A. Healy, S. Kosslyn, & R. Shiffrin (Eds.), From Learning Processes to Cognitive Processes: Essays in Honor of William K. Estes (Vol. 2, pp. 35-67). Free PDF from authors

Researcher's Note: This theoretical paper introduced the concept of desirable difficulties: challenges during learning that slow initial performance but enhance retention. The Bjorks argue that making retrieval harder (within limits) strengthens memory traces. This framework explains why spacing, testing, and other effortful strategies outperform easier alternatives.

8. Roediger, H.L., & Karpicke, J.D. (2006). "The Power of Testing Memory: Basic Research and Implications for Educational Practice." Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(3), 181-210. Free PDF from authors

Researcher's Note: This review article demonstrates that retrieval practice (testing yourself) is a more powerful learning tool than most educators or students realize. The testing effect works across ages, materials, and retention intervals. Importantly, students often feel more confident after re-reading than after testing, even though testing produces superior retention.

9. Samani, J., & Pan, S.C. (2021). "Interleaved practice enhances memory and problem-solving ability in undergraduate physics." npj Science of Learning, 6, 32. Free full text

Researcher's Note: This study showed that mixing different types of physics problems (interleaving) during practice produced 50-125% better test performance than practicing problems in blocks by type. Students rated interleaved practice as more difficult and incorrectly predicted they learned less from it, demonstrating how our subjective judgments about learning are often wrong.

Published: 12/31/2025

Last Updated: 02/06/2026

Newest / Popular

Multiplayer

Board Games

Card & Tile

Concentration

Math / Memory

Puzzles A-M

Puzzles N-Z

Time Mgmt

Word Games

- Retro Flash -

Also:

Bubble Pop

• Solitaire

• Tetris

Checkers

• Mahjong Tiles

•Typing

No sign-up or log-in needed. Just go to a game page and start playing! ![]()

Free Printable Puzzles:

Sudoku • Crosswords • Word Search

Hippocampus? Working memory? Spaced repetition?

Look up memory or brain terms in the A-Z glossary of definitions.